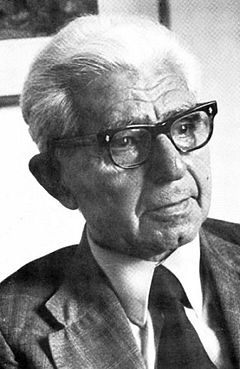

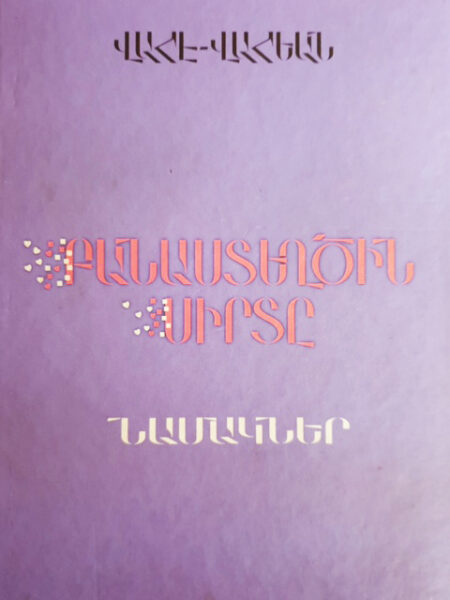

The world of Armenian literature is all the richer for the compilation of renowned poet Vahe-Vahian’s private letters, published posthumously in 2012, under the title The Heart of the Poet. The 441 letters assembled in the hefty volume are divided into three sections: letters of literary and aesthetic interest, letters dealing with national and public issues, and more intimate exchanges.

I would like to focus here on the seventy or so love letters which can be thought of as works of art, displaying the same mastery of our kaghtsrahoonch Western Armenian, Vahe-Vahian knew so well and loved so well, as do his other writings. In these letters the poet opens his heart to expose, in his words, “all that is true and pure in there.” Indeed, with their audacity and their sincerity, the love letters reaffirm the veracity of the remaining conversations the poet has with fellow writers, which comprise the bulk of the compilation. Even when it means hurting the feelings of, and possibly losing, a good friend, Vahe-Vahian offers honest criticism of the work submitted to him, not only to help and to guide the writer, but also because his desire for the truth supersedes every other consideration. Aram Sepetjian, editor of The Heart of The Poet, rightly notes: “These letters are documentation to his literature.”

When I shared my excitement about his father’s love letters with Tsolak Abdalian, “You sound like you’re going to write about them,” said Tsolak. Nothing could have been further from the truth at the time. Yet, the idea had taken seed in my mind. I had always revered my high school Armenian language and literature teacher. I had also known the poet, and admired the critic and the translator. The fervent lover, however, was someone I did not even imagine existed. These exquisitely written letters revealed to me the passionate lover as well.

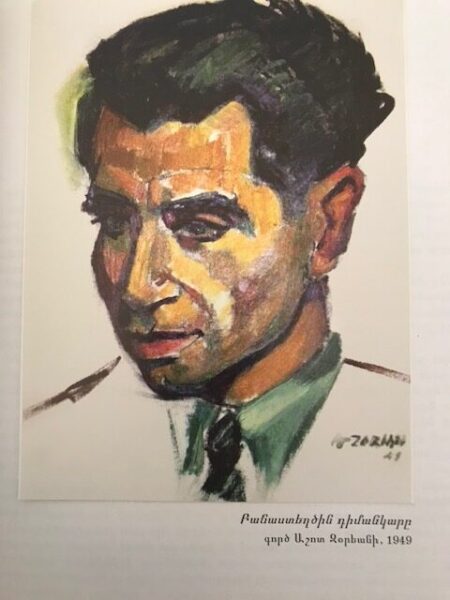

Included in the volume are the letters addressed to the women Vahe-Vahian had intimate relationships with, roughly stretching across the years 1932 to 1952. These include the earlier letters to Siran Seza, pen name for Siranoush Zarifian, best known in the Lebanese Armenian intellectual community for founding the feminist journal The Young Armenian Woman, in 1932, and later missives addressed to his wife, and mother of his three children, Ashkhen Abdalian, a fellow teacher he met at the Melkonian Educational Institute in Nicosia, Cyprus.

The letters to “Siran Janig” express the poet’s intoxication with “the girl with the sad liquid eyes.” These letters are full of images of “the sun caressing the blue Mediterranean,” his tiny room at Broummana High School, where he taught in the early 1930’s, overlooked. The bold lover invites “my sweet Siran” to his village, to “the peace of nature.” Besides his burning desire for “the fairy-tale girl,” however, the letters reveal the hurt of his betrayal. Indeed, the letters expressing his wrath at “my impossible lover” are some of the fiercest addressed to Siran. “I hear the obscene wind torturing the trees and giggling. I hear the sound of waves shattering into pieces,” he writes, as he waits for “a miracle to happen for Siran to show up.”