BELMONT, Mass. — The headline above may be a simplification of the new book, Everyday Cosmopolitanisms: Living the Silk Road in Medieval Armenia, by Dr. Kate Franklin. However, the idea that everyday life can be cosmopolitan or, to hew closer to Franklin’s perspective, the idea that everyday life is an integral part of what are often thought of as overarching worldwide systems, was one of the takeaways from her October 31 talk, sponsored by the National Association for Armenian Studies and Research (NAASR) and London’s Armenian Institute.

Franklin is an archaeologist and professor in the Department of History, Classics, and Archaeology at Birbeck, University of London, where she is the director of the Master’s Program in Medieval History, as well as the director of studies in the Department of History, Classics and Archeology, and lecturer. The Zoom lecture, coordinated by Marc Mamigonian of NAASR and with Dr. Nik Matheou of the Armenian Institute as discussant, focused on the themes in her new book.

Franklin, she explained, has been interested in the stories of the fabled Silk Road since she was young. A network of trade routes that links China with Europe in the Medieval era, the Silk Road has been the subject of romanticized accounts since the time of Marco Polo, and gained popularity as an academic subject in the 19th century as Western Europeans travelled the world in the era of Imperialism. The traditional narratives often depict intrepid travelers (European or otherwise) trekking to exotic lands; generally males from an elite class. Franklin’s goal seems to be to show that women and lower socio-economic classes were part of the Silk Road story as well, even if they weren’t making trips from Venice to Inner Mongolia, and aspects of everyday life like meals were just as important to the international silk trade as the silk itself.

Franklin opened her talk with a story that will resonate even with Armenians that have never set foot in Armenia; while on a journey to a small village inspecting medieval ruins, she came across a middle-aged Armenian woman who insisted she come into the house and eat, even to the point of unwrapping small chocolates and putting them on her plate. The story exemplified Franklin’s realization of the importance that food, hospitality, and the lives of women must have had to anyone travelling long distances in the Middle Ages. By the same token, the lives of people who lived along trade routes could be just as cosmopolitan as that of the merchants and travelers, due to the cultural interchange that was constantly taking place.

Both Franklin and Matheou touched upon the prevalence of “World Systems Theory,” an overarching paradigm for world history which emphasizes the “world system,” particularly in an economic role, rather than nation-states. Franklin expressed her wish to provide a counter to that kind of analysis, not to refocus on the nation-state, but to emphasize the local and particular.

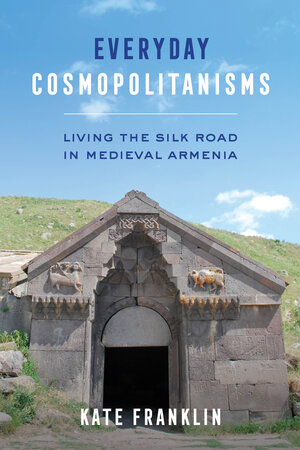

Much of Franklin’s attention has been directed to the role of caravanserais (roadside inns) which served as accommodations for trade caravans. The best-preserved caravanserai in Armenia today is the Orbelian Caravanserai in the Vayots Dzor region, which graces the cover of Franklin’s book. However, in her talk, she focused on Arayi-Bazarjik Caravanserai, in the Kasakh Valley region north of Yerevan (near Abaran). This structure was built by the princely Vachutian family. Travelers to Armenia will likely have visited the family’s seat of power, Amberd Fortress.