ITHACA, N.Y. — The organization Caucasus Heritage Watch (CHW), in a year-long forensic investigation, using high-resolution satellite imagery, has documented the fate of Armenian cultural heritage sites in the Nakhichevan Autonomous Republic of Azerbaijan. CHW, based in Cornell University, is also conducting research on the Armenian heritage sites in Artsakh.

A shortened version of the report appears below.

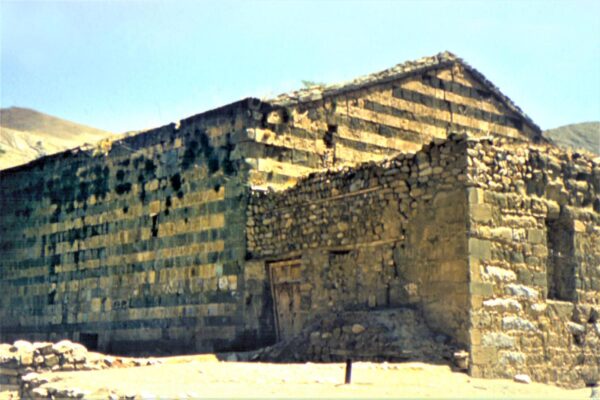

CHW’s research shows the complete destruction of 108 medieval and early modern Armenian monasteries, churches, and cemeteries between 1997 and 2011. This figure represents 98 percent of the Armenian cultural heritage sites we were able to locate and assess for this investigation. These findings provide, for the first time, conclusive forensic evidence that silent and systematic cultural erasure has been a feature of Azerbaijan’s domestic ethnic policies.

The long history of Armenians in Nakhichevan is well-documented in the region’s archival, architectural and archaeological records. Their numbers diminished over the course of the Soviet period, dwindling to just under 2000 by 1989. Following the Soviet Union’s collapse in 1991, and an outbreak of conflict between Armenians and Azerbaijanis, the number of Armenians in the region diminished to zero.

Although the destruction documented in this investigation occurred years ago and elicited little global attention, these findings remain of urgent relevance today. Ethnic conflict between Armenians and Azerbaijanis continues to define the region’s political and cultural landscape. Following the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War in 2020, separatist Armenian forces ceded territory to the Azerbaijani state that they had held for 30 years, in the process relinquishing control over hundreds of additional monasteries, churches, and cemeteries — some located just 75 kilometers from Nakhichevan.

There is reason to fear that the template for cultural erasure in Nakhichevan will be pursued in the Nagorno-Karabakh region, too. CHW has already documented the beginnings of a similar pattern, with 6 confirmed destroyed, 7 confirmed damaged, and 17 threatened just since the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War began in September 2020. In December 2021, partly based on CHW’s reports , the International Court of Justice determined that attacks on Armenian cultural heritage in Azerbaijan plausibly constitute violations of the International Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Racial Discrimination; it ordered the government to “take all necessary measures to prevent and punish acts of vandalism and desecration affecting Armenian cultural heritage….” (Two months later, Azerbaijan’s Minister of Culture announced a plan to erase Armenian inscriptions from monasteries and churches.) This March, the European Parliament condemned “Azerbaijan’s continued policy of erasing and denying the Armenian cultural heritage in and around Nagorno-Karabakh.”