SAN FRANCISCO — Heritage pilgrimages to Historic Armenia and other parts of Turkey once populated by Armenians have become more and more common in recent decades, especially thanks to the efforts of pioneer tour leader Armen Aroyan, but academics and serious commentators have paid little attention to this phenomenon.

At a time when the fate of Artsakh or the current regime in Armenia and issues of the remaining Armenian community in Istanbul are considered more important, these heritage pilgrimages may be viewed as simply pleasure trips by well-to-do Armenian-American tourists to their ancestral villages, and as such are relegated to the status of a hobby. Not so, according to new book.

Ironically, the Armenian Genocide and destruction of Armenian life in Turkey is not only being continually denied by Turkey but also relegated to the dusty pages of history by those who wish to turn our attention, however understandably, to the needs of the current Republic, sometimes trivializing the historical experience of the Diaspora in the process. But a new book shows how American-Armenian heritage tourists (or “pilgrims,” as the author insists on referring to them) are, in a way, the last remaining witnesses to what was once the vibrant Armenian life of current-day Eastern and Central Turkey.

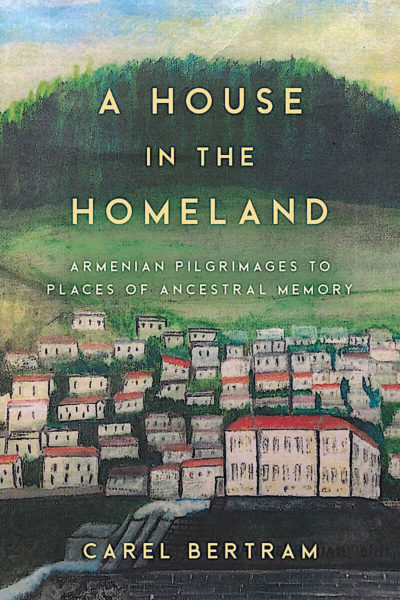

Carel Bertram, emerita professor in the Humanities Department of San Francisco State University, has championed the story of heritage pilgrims in her new book, A House In the Homeland, Armenian Pilgrimages to Places of Ancestral Memory (Stanford University Press, 2022). She is a fierce advocate for the survivors and descendants of the Armenian Genocide to lay claim to their historical existence in lands that are now part of the modern Republic of Turkey.

When Bertram first went to Turkey, she found something other than what she expected. The breezy art historian from California, of Sephardic Jewish descent, was fascinated by the domestic architecture of late-Ottoman houses. Travelling to interior towns with surviving 19th-century neighborhoods, she couldn’t stop asking questions about these fascinating abodes. She was surprised to learn that many “well-to-do Ottoman citizens” who originally lived in such houses turned out to be Armenians. She was further surprised that the Turkish government was still adamant in discussing this fact.