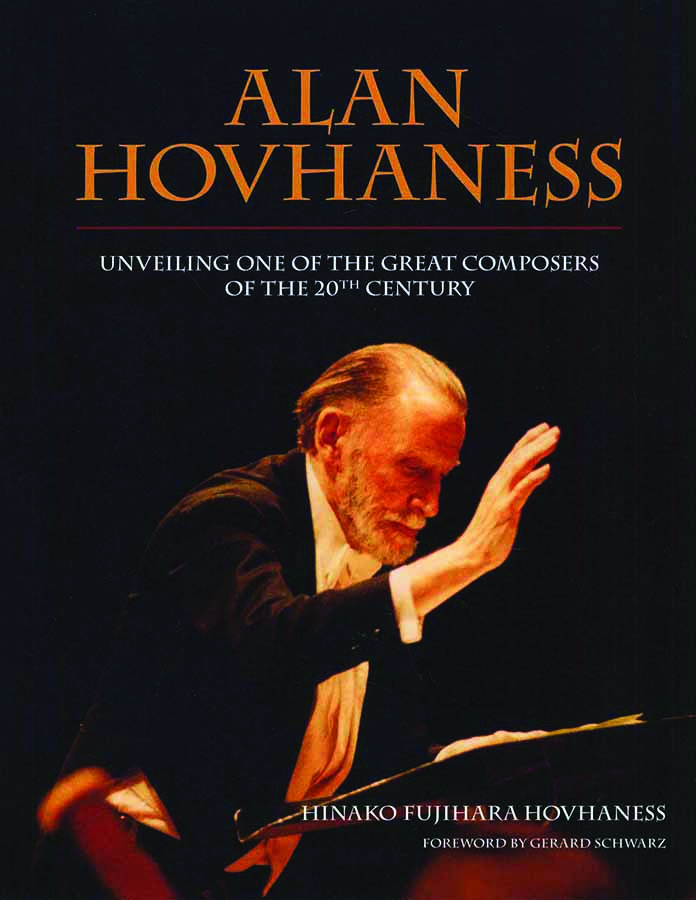

Hinako Fujihara Hovhaness’s Alan Hovhaness: Unveiling One of The Great Composers of The 20th Century (Classic Day Publishing, 2025) tells the story of a composer championed by some of the greatest conductors and music professionals of the 20th century. Leslie Heward, principal conductor of the BBC Midland Orchestra premiered Hovhaness’s first Symphony, Exile, in 1939. In 1943, the world-renowned conductor Leopold Stokowski performed Exile with the Los Angeles Philharmonic and commissioned Hovhaness’s second symphony, Mysterious Mountain, which he premiered with the Houston Symphony for his inaugural concert in 1955.

“Alan’s every premiere was a joyous occasion,” writes Hinako.

When the Cleveland Orchestra first performed Mysterious Mountain in December 1957, “Here was a modern piece full of melody and pleasant to the ear. No dissonance, no noise, no discord, just beautiful sweeping harmony,” wrote the Cleveland News. On a similar note, the acclaimed Jazz pianist Keith Jarrett commented on the “profound simplicity” of Alan’s 1944 Piano Concerto Lousadzak (The Coming of Light in Armenian) which he recorded in 1989 with the American Composers Orchestra.

While full of fascinating details about Alan’s premieres, his concerts and his relationships with other composers and conductors, Alan Hovhaness: Unveiling One of The Great Composers of The 20th Century is not about the composer’s music. The book is about the man behind the music. The project may have originated in the short poems Hinako started composing to bring back into her life the man she could not conceive of living without when she lost Alan in the year 2000. Alan and Hinako, the coloratura soprano he met at a piano recital in 1974, were married in 1977 when the composer was in his late 60s and she in her 40s. Writing down the stories Alan had told her about his life and her own vivid recollections of events she had experienced with Alan helped keep the man she “adored passionately“ close to her, she avows.

The story Hinako weaves of the passion, the devotion and the deep commitment she and Alan had for each other reads like a true love story. Alan’s January 22, 1983 note to Hinako, “I will be a faithful husband to Hinako all my life. If I fail I agree to be killed” does not sound deceptive. Indeed, his ”I will be with you in spirit” and her “In spirit, I will see him again; that is my salvation and hope” is consistent with everything the two believed.

Both Alan and Hinako were spiritual people. Alan was inspired by the majesty and the mystery of mountains and had visions on the top of mountains in his early childhood. When the Cleveland Orchestra performed Mysterious Mountain in 1957, “His music evokes an atmosphere of spirituality not often heard in contemporary music,” wrote critic Herbert Elwell in the Cleveland Plain Dealer.