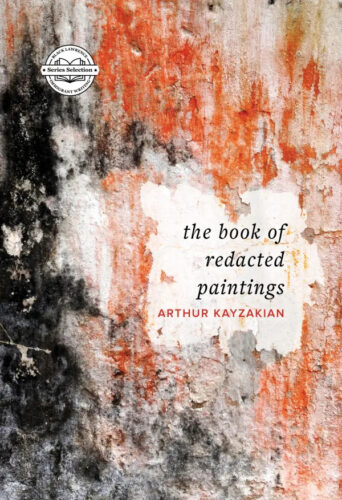

With his “The best translation of/darkness is a victory flag,” Arthur Kayzakian divests the victory flag of its connotations of glory and joy and makes the book of redacted paintings (Black Lawrence Press, 2023) an indictment of all displacements, all erasures and all wars. The persona in the poems assembled in the slim volume is trying to write his way through to his homeland. With images that reach deep into the consciousness, Kayzakian awakens the reader to the horrors of an “invasion” that took the persona’s whole world away from him. The exiled son’s yearning “to get back to my world,” yet failure to reclaim what he has lost, underscores the enormity of the crime committed against him. His “Dear Reader,/Today I haven’t thought about killing myself” conveys his despondency about the reality he now has to exist in.

It is through the search for a missing painting that the poems explore this “upside-down world.” All that the search brings to light, however, is that the portrait, “My Father Under the Stars, 1979,“obviously, of my father” standing by a redwood, “cannot be recovered.” After numerous letters back and forth with The Art Restoration Center and the FBI, the son is courteously asked to “take your endeavors elsewhere.” Indeed, because of the “unusual request for a painting redacted from reality,” The Art Center takes “the liberty to include our Trauma, Loss and Therapy Department for further counseling” in their response to his quest. The sarcastic tone of the persona’s “This painting does not exist, but in some version of this story, it was stolen in winter, the season my father was late from the war,” cannot be missed. In “Stain on the Wall,” a poem that can be said to encapsulate his vision, Kayzakian writes:

when potential buyers

arrive touring the house