BELMONT, MA — March 15 was referred to by the Romans as “the Ides of March.” A day for settling debts, it became infamous as the date of the assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 BC. Whether or not this day was chosen on purpose by the planners of Operation Nemesis or it was a coincidence, it was also the day that Talaat Pasha, de facto dictator of Ottoman Turkey during the First World War and chief perpetrator of the Armenian Genocide, was gunned down by Soghomon Tehlirian in 1921 on a Berlin street in an act of vigilante justice carefully planned and executed.

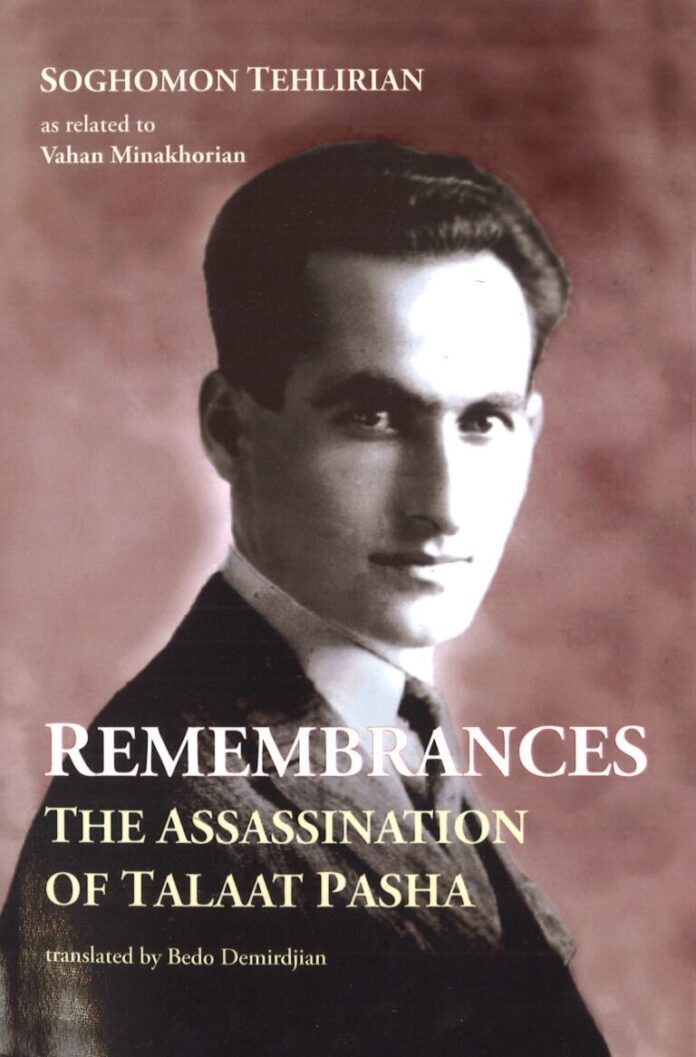

On March 15 of this year, a virtual talk was sponsored by the National Association for Armenian Studies and Research (NAASR) with the participation of the Ararat-Eskijian Museum and the Armenian Film Foundation on the publication of Remembrances: the Assassination of Talaat Pasha, featuring translator Bedo Demirdjian and documentary filmmaker Carla Garapedian. Remembrances is the first-ever translation into English of Soghomon Tehlirian’s memoir, Verhishoumner, originally published in Cairo in 1953 by the publishing house of Housaper, the ARF’s affiliate newspaper in Egypt.

While the court proceedings of Tehilirian’s Berlin trial (where he was found innocent) and numerous historical and artistic works have been created in the years since the historic assassination, including Eric Bogosian’s popular history Operation Nemesis and Marian MacCurdy’s Sacred Justice, which brought to light the invaluable documentation in the personal papers of her grandfather, Aaron Sachaklian, to date nobody had translated for publication in English the entirety of the only book that could sufficiently tell the true story in its entirety: Verhishoumner, the memoir of Tehlirian himself.

As explained in the talk, the genesis of this project came about when Garapedian became interested in making a feature film about Tehlirian. Garapedian, a former television newscaster and producer who was the first American to anchor BBC World News, has in the past two decades made a name for herself as a documentary filmmaker. Her film, “Screamers,” released in December 2006, used the music of rock band System of a Down to explore the horrors of Genocide in the 20th century, including the Holocaust, Bosnia, Darfur, Rwanda, and of course, the Armenian Genocide.

She is also closely connected with the Armenian Film Foundation, which was started by her father Leo Garapedian to support filmmaker J. Michael Hagopian in his efforts to document on video the stories of Armenian Genocide survivors. After the death of Hagopian, Carla Garapedian took over as project leader of the Armenian Genocide Testimonies collection which digitized these videos to be stored in the Shoah Foundation’s Visual History Archive, a project spearheaded by Steven Spielberg, based at the University of Southern California.

Demirdjian was born and raised in Beirut and attended school at the now-closed Melkonian Educational Institute in Cyprus followed by university in Greece. Having worked as a journalist and communications director for the Armenian National Committee – Europe as well as for the Permanent Representative of Artsakh to the Middle East, he settled in Armenia in 2020 where he headed the Children of Armenia Fund (COAF) Smart Center in Lori and currently lives in Yerevan where he works as the communications director for the Tufenkian Foundation.