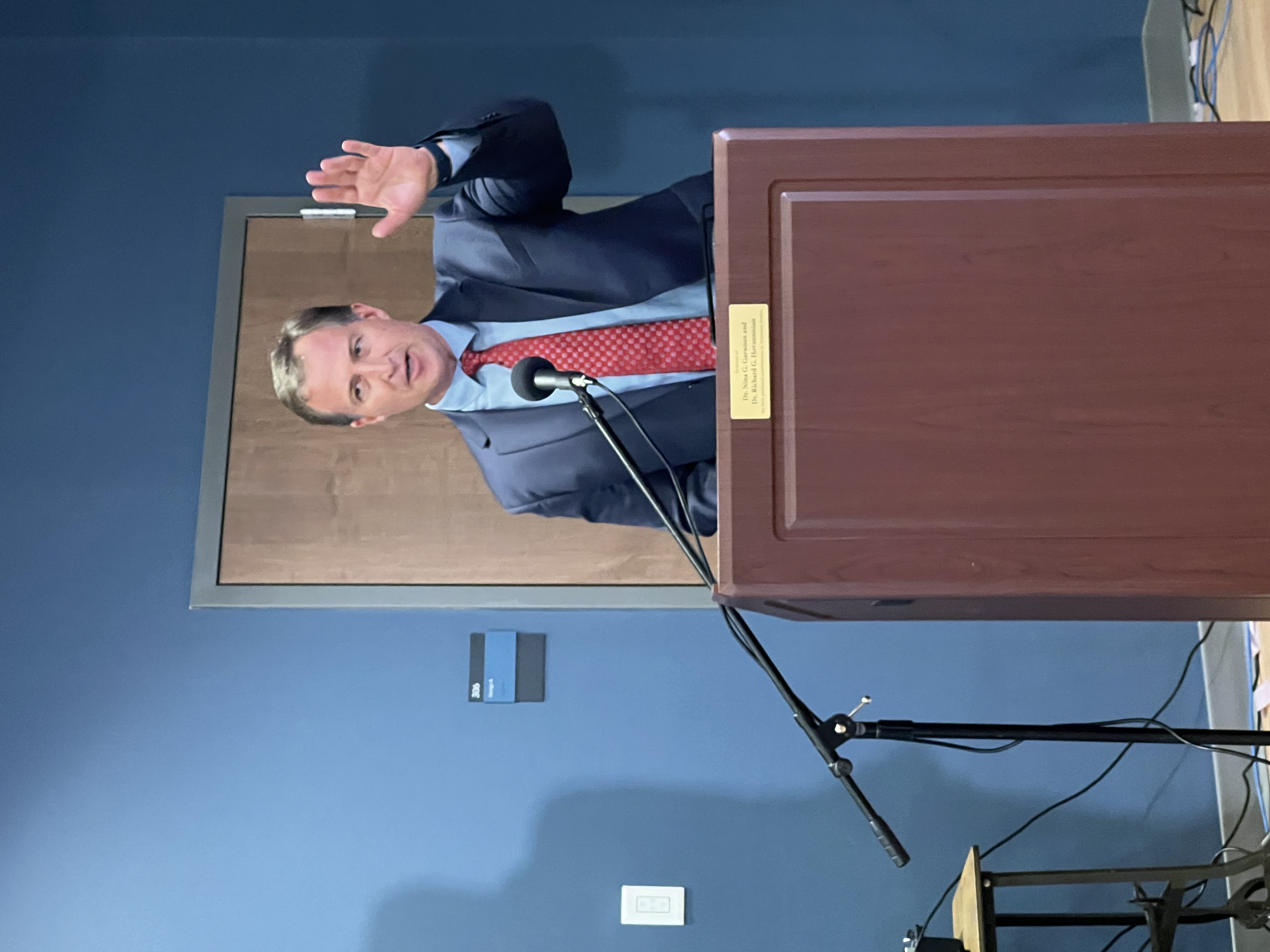

BELMONT, Mass. — The Armenian Assembly of America, currently commemorating its 50th anniversary, invited its members to attend a conversation with distinguished career US diplomat Edward Djerejian at the National Association for Armenian Studies and Research (NAASR) headquarters on November 13. This was apparently Djerejian’s first public appearance in the Boston area since he and his wife Françoise moved here.

The audience was first welcomed on behalf of NAASR by its executive director, Silva Sedrakian, and by chair of the NAASR Board of Directors Judith Saryan, before Anthony Barsamian, co-chair of the Assembly’s Board of Trustees, spoke briefly of his organization’s 50th anniversary commemorations and its purchase of new office space before introducing Djerejian.

Barsamian pointed out how remarkable a resource for the Armenian community Djerejian is, having served eight US presidents, starting with John F. Kennedy. Aside from serving as US ambassador to Israel, ambassador to Syria, and Assistant Secretary of State for Near Eastern Affairs (1991-1993), Djerejian served in diplomatic posts in Jordan, Morocco, Lebanon, France and Russia. Most recently, he was the founding director of Rice University’s James A. Baker III Institute for Public Policy.

An Armenian Goes to Washington and then Abroad

Assembly Board of Trustees President Carolyn Mugar began the conversation with Djerejian by asking him how his background as an Armenian-American shaped his thinking as a diplomat.

Djerejian said, “You bring your background to whatever you do and I think that being Armenian of the first generation of the Genocide, born in New York, you have a sense of history, not intellectually but through osmosis.” The fact that his parents survived that tragedy gave him, he said, “That feeling that you have an extra responsibility, and the other thing that — and again, this is not intellectual but it was more motive — I should give back to this country that gave safe haven to my parents and allowed us to grow up here. So I decided to go into the Foreign Service.”