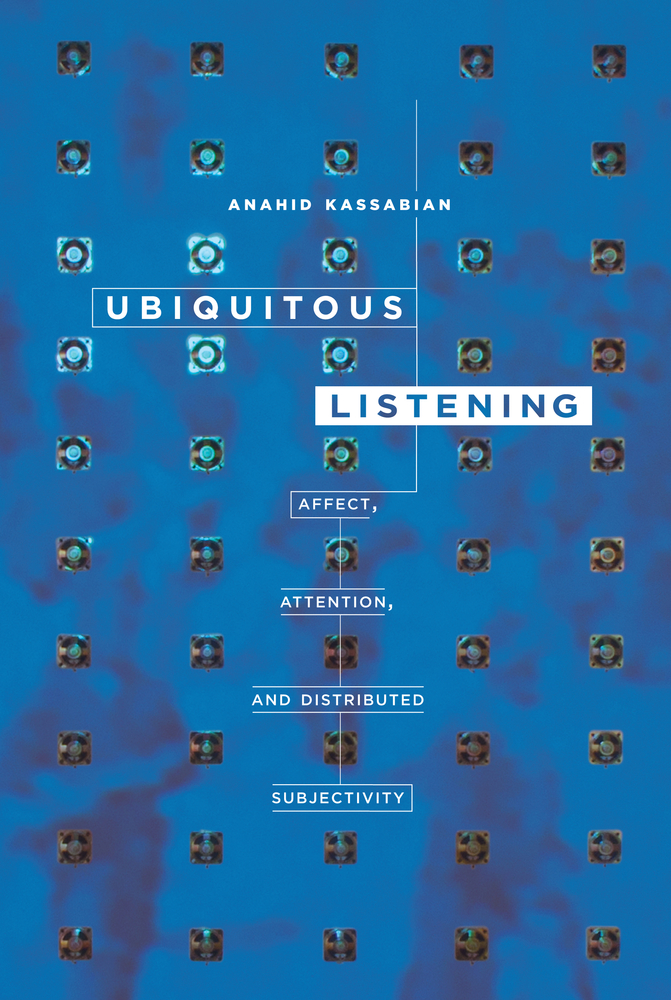

Few books shine quite so spectacularly as Anahid Kassabian’s ground-breaking Ubiquitous Listening: Affect, Attention, and Distributed Subjectivity. Kassabian has held important positions in academia, including the James and Constance Alsop Chair of Music at the University of Liverpool and previously chaired the Literary Studies Program at Fordham University in New York City. Published in 2013 by The University of California Press, this slim but powerful volume introduces readers to innovative new ideas while repositioning the field of music study itself in light of post-Kantian philosophy. Taking a cue from distributive computing, Kassabian takes music analysis from a purportedly objective position to a more pluralistic, distributive “we/they.” It’s an important distinction which posits that we listen or hear in a distributive way, partially at times and more attentively at others. Yet we always remain apart from the music itself and an “other place(s)” that it takes us to — sometimes simultaneously. By theorizing Muzak and the music — or noise — that one hears every day in places like Starbucks and department stores, Kassabian manages to introduce an entire new field of study — her second or third such prestidigitation — while calling attention to the background music that we usually dismiss. Along the way she also beautifully analyses the work of three Armenian video artists — Diana Hakobyan, Sonia Balassanian, and Tina Bastajian, placing an emphasis on the aural/sound track as much as the visual elements in each video. She then turns her attention to three Armenian jazz bands — The Armenian Navy Band, Night Ark, and Taksim — and explains how her relationship to these three internationally renowned music groups helped her to re-insert herself into an Armenian culture that she had turned away from because of its conservative and patriarchal nature.

Kassabian’s ability to weave Armenian culture in and out of otherwise mainstream observations and analyses is the least of her talents. After finishing her book, I found myself paying special attention to the music that surrounds me — at Starbucks, in my local pizzeria, and overheard on speakers on the A Train — paying special attention to sound, now ubiquitous, now everywhere. The point, of course, is that the music has always been there, we just usually integrate it into our everyday experience to the point that we don’t notice it anymore. And hidden away in our everyday experience of ambient or ubiquitous hearing is a fascinating double history — one “hi” and one “lo” — in mainstream terms. The “hi” version takes us back to the turn of the 20th century and French composer Erik Satie’s “Musique d’ameublement” and on up through John Cage who with his partner, the choreographer Merce Cunningham, emphasized environmental sound.

The other parallel, “lo” history belongs to General George Owen Squier who created Wired Radio — or Muzak as we now know it — and its many “stimulus progression patents.”

Though Kassabian does not quite position him thus, I kind of see Brian Eno as navigating a fascinating world between the Saties and Cages on the one hand, and Muzak on the other.

Along the way, Kassabian also considers films such as the Wachowskis’ “The Matrix” series and “Lara Croft: Tomb Raider,” where often computer-simulated image and sound, rather than traditional plot and acting, propel the action forward. While these are not always the most felicitous adventures in the cinematic arts, they are definitely a new trope or type of filmmaking, perhaps in parallel with more traditional modes of cinema on the one hand, and completely experimental ones on the other.

In a related instance, Kassabian looks at the veritable onslaught of campy musical episodes in TV series such as “Family Guy” and “Buffy, the Vampire Slayer,” which helped in the mid-1990s to mid-2000’s in recapturing viewer attention after a period of what I call “TV fatigue.”