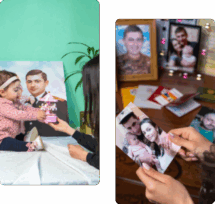

YEREVAN — “A year from now, they might not remember you, or even remember your face, but they will remember for the rest of their lives that act of kindness,” says Alex Ouzounian, one of the organizers of the Artsakh Relocation Project. Ouzounian is part of a team of 8 young diasporans, all in their 20s and 30s, living in Armenia and the United States, who have started an initiative to fulfill the immediate needs of some of the many thousands of refugees who have poured into Armenia proper from Artsakh.

Ouzounian, a third-generation Armenian-American from Racine, Wis., who has been living in Armenia for about two years, temporarily left his teaching position in Yerevan to spend all his time on the Artsakh Relocation Project. In only a couple of weeks, they have already reached some 20 families, supplying them with food, groceries, cleaning supplies, clothing, and even paying for rent and utilities.

It all started before the war was even over, when Ouzounian opened his own GoFundMe page to raise money for refugees. The page, which is still active, states that the proceeds will be divided equally between three projects: the Homeland Development Initiative Foundation, through which women in rural areas of Armenia will be paid to make winter clothing that will be distributed to Artsakh families; the Fund for Armenian Relief (FAR) to buy essential items for Artsakh refugee families, and for Ouzounian and his small team to distribute personally to refugee families.

Ouzounian’s reason for taking matters into his own hands was that “politically speaking, NGOs might have to work slower,” in order to fulfill certain legal requirements. Larger NGOs cannot handle the amount of refugees entering the country. As an example, Ouzounian says, “Today we got food and clothing to four families. One of them called us and said we have nine people in the house.”

Some of these families have needs so immediate that they might otherwise starve. Team member Avetis Chekmeyan delivered food to a family taking refuge in the village of Masis, comprising a mother, grandmother, and six kids. The woman told Chekmeyan, “I’m so thankful for what you’re doing, because we haven’t eaten today.” It was 7:00 pm.

An International Diasporan Team