By Arman Khachatryan

Special to the Mirror-Spectator

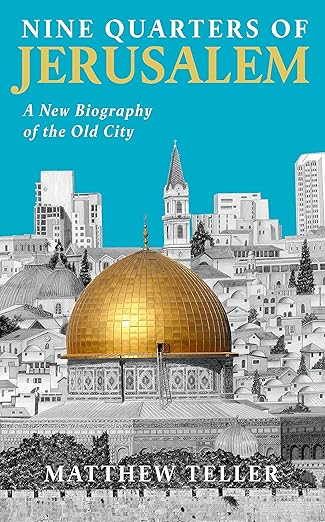

Matthew Teller’s Nine Quarters of Jerusalem: A New Biography of the Old City (London, UK, Profile Books, 2022, 385 pp., US$27.99 hardcover, ISBN 978-1635423341; US$10.81 paperback, ISBN 9781788169196) can be considered a piece of urban anthropology. While the author obviously did not have academic intentions when writing the book, he attempts to unlock Jerusalem’s gates by combining his background as a traveling journalist with the accuracy of a researcher. Teller grounds the stories in historical facts, not as an end but as a means to explore their effects on the present and future. His reference to the history of the city’s various faces and parts highlights its impact on the existing and future state of urban life, demonstrating the unavoidable influence of the past on the lives of its residents.

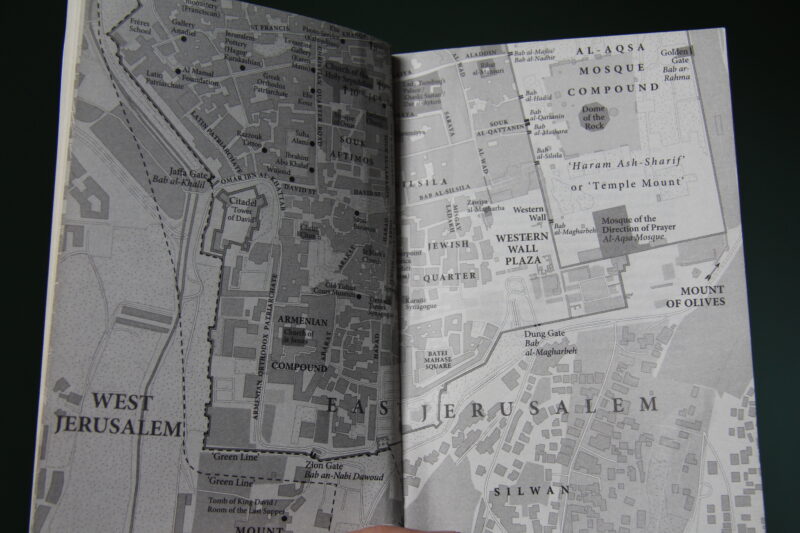

Among the many books written about Jerusalem in a similar genre, this one stands out due to two new approaches introduced by the author. In particular, the author’s main goal was to amplify the voices of the ethnically and religiously marginalized communities of Jerusalem, as well as their experiences of living in the city. In the whirlpool of the dominant Jewish and Palestinian presence and narratives, these voices have remained largely unknown to outsiders. To achieve this, Teller first conducts historical research to determine the origins of the traditional division of Jerusalem into four quarters, which he initially subjects to severe criticism. He discovers that the practice of dividing Jerusalem into neighborhoods and quarters on maps became widespread at the start of the 19th century when European countries began entering the Ottoman Empire. Teller notes that the first map of Jerusalem depicting religiously defined quarters was published in 1837 by the Viennese lithographer Hermann Engel. Engel essentially translated into German the map of Jerusalem created two years earlier by the English explorer-architect Frederick Catherwood, while also introducing new elements, such as ethno-religiously defined districts. Teller further points out that the first explicit division of the city into four parts on a map is attributed to chaplain George Williams, who included a map created in 1841 by Aldrich and Symonds in his 1849 edition titled The Holy City.

Teller sees the traditional division of Jerusalem into four quarters as a consequence of the British Empire’s colonial policy, calling them colonial-era quarters. He argues that, to this day, historians and researchers have legitimized the colonial model of dividing the city into four by continuously repeating this phenomenon without questioning it. Criticizing this approach and aiming to serve as a voice for the small and marginalized religious and ethnic groups living in the city, the author claims that beyond the traditional division of Jerusalem into four colonial-era quarters, the city also includes five lesser-known quarters: Sufi, Roma (Dom or Gypsy), Kurdish, Magharibah (Moroccan), and Bab al-Majlis neighborhood. Teller makes it clear that there may be nine quarters in Jerusalem — hence the title of the book — or even more, as many as there are ethno-religious groups, such as the Karaite Jews living in the Jewish Quarter, who are not considered Jewish by Israel’s Chief Rabbinate (245). His surprise is palpable when questioning which quarter Jaffa Gate falls into — Christian or Armenian: “What a mad question! As if Armenians weren’t Christians” (15).

Maps can express the imaginary, yet they mostly depict rational realities. I contend that the Armenian Quarter of Jerusalem acquired its current shape and structure long before any European country entered Jerusalem during the Ottoman period. In contrast to the author’s hypothesis — that the division of the city is solely a consequence of European colonial foreign policy — he himself acknowledges references to other neighborhoods and quarters of Jerusalem dating back to the 15th century [29]. Turning to the Armenian case, the first evidence of the Armenian Quarter in Jerusalem dates back at least a millennium. The Armenians were among the earliest pilgrims and religious settlers in Palestine, arriving shortly after Christian holy sites were identified in the 4th century, soon after Armenia became the first country to officially adopt Christianity. The discovery of seven mosaic floors bearing Armenian inscriptions, dated as early as the 5th century and found around Jerusalem, confirms that Armenians were among the pioneers in identifying and establishing sacred places in and around the city. From that time onward, Armenian clergy began constructing religious institutions and monasteries, gradually forming what is now known as the Armenian Quarter of Jerusalem. By the time of the Crusades, a well-established Armenian community already existed in what is now the southwestern part of the Old City. Kevork Hintlian, a Jerusalem-born historian and one of Teller’s interviewees, notes in his History of the Armenians in the Holy Land (Jerusalem: St. James Printing Press, 1989) that European travelers such as John of Würzburg, who visited Jerusalem in 1161, testified to the existence of the Armenian Quarter [19]. Another European monk cited by Hintlian mentioned that during the Crusades, the Armenians occupied a substantial section of the city, with a long street known as Ruga Armenorum, a name it had retained since Byzantine times, along with numerous churches [ibid.] The Armenian Quarter expanded over time to accommodate not only local monks residing near Saint James Monastery but also the many Armenian pilgrims and merchants who visited Jerusalem annually—many of whom remained for extended periods.