The United States of America has been portrayed as the land of freedom and opportunity, a refuge for the oppressed and the poor. Immigrants from all over the world come to America and struggle to create a new life. Stories of individual success abound. Dr. Dennis Papazian’s journey is a classic example. In his recently published memoir, From My Life and Thought: Reflections on an Armenian-American Journey (Fresno State Press, 2022), Papazian chronicles his struggles of “trying to fit in and be accepted,” first in the provincial town of Augusta, Ga., where he was born less than two decades after the Armenian Genocide, and later in Detroit, Mich. The “poor immigrant boy” is well-aware of his lack of privilege in a culture where ethnic minorities are marginalized. Yet, with hard work and perseverance, he overcomes obstacles and rises to key leadership positions in the Armenian-American community.

The success stories of individuals do, nonetheless, raise questions about the many more who fail to realize their potential because of, in Papazian’s own words, “unofficial segregation” and legalized restrictions. The popular melting pot metaphor for a land where “all are created equal” is, in fact, perceived by many as being deceptive. Noted educational critic Jonathan Kozol writes of the “educational apartheid” of the “Still Separate, Still Unequal” school system in the United States. On a similar note, the late Mike Rose, professor in the School of Education at UCLA, writes of school administrators limiting educational opportunities to students in the vocational education track by instilling in them the “I just wanna be average” mentality.

The disparity between the promise and the reality of a land that advertises herself as the land of equality and harmony, has been exposed by Diaspora writers of all ethnic backgrounds. The Book of Khalid by Lebanese-American writer Ameen Rihani, the story of two immigrants from the village of Baalbek in Lebanon, who at the turn of the century sail “West — to the paradise of the World — to America . . . the land of equal rights and freedom,” depicts their disenchantment and the dehumanizing immigration process at the Bureau of Emigration in the “Juhannam of Ellis Island.” “Are you sure we are better off here?” Khalid asks his friend repeatedly.

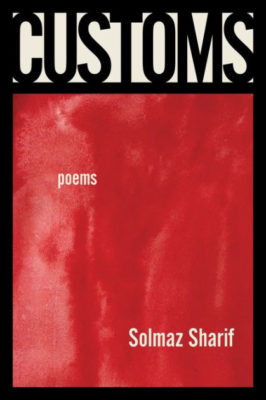

Among the more recent voices desperately searching for the truth in “a counterfeit universe,” is the voice of poet/musician Alan Semerdjian. “Oh Truth where is your hide? Why must we seek you in the debris?” pleads Semerdjian. Solmaz Sharif, on the other hand, the 39-year-old, multiple-awards-winning Persian-American poet, makes us question the very premise of America as a land where all are welcome. “I am without the kingdom . . . even when inside the kingdom — /without . . . A without which/I have learned to be,” writes Sharif in “Without Which,” a poem in her newly released book of poems, Customs (Graywolf Press, 2022). Even immersion in English, believed by many to be the mark of success for a foreign-born, is seen by Sharif as capitulation to “A world polite/for their words,” to a world that thrives on control, language being an important part of that control: “To finally admit out loud then, I want to go home/ . . . To lament the fact of your lamentations in English, English being/your first defeat.”

For Sharif, being uprooted from one’s land and coming to America is not about being torn between two traditions. It is about leaving something behind for a culture where one is always alone, always excluded. The persona in the poems refuses to see “The Master’s House” as her source of support. At a time when it is fashionable to define identity as a process, in other words, as something that is continually changing and forming, and therefore as allowing the individual to always feel “included,” Sharif depicts the endless going from gate to gate at airports — “All my waiting at the railing”—as an experience that inevitably leaves one “without.” In “He, Too” she writes:

Upon my return to the US, he