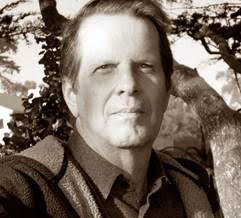

By Steve Hauk

PACIFIC GROVE, Calif. — The following remembrance of William Saroyan and John Steinbeck by journalist and writer Steve Hauk first appeared at SteinbeckNow.com on June 19, 2021. Steinbeck Now is an independent information resource with no institutional affiliation. It is a not-for-profit, non-commercial educational portal developed to benefit the public. It accepts original articles and art with a fresh, transformative perspective on Steinbeck’s life, thought, and persona.*

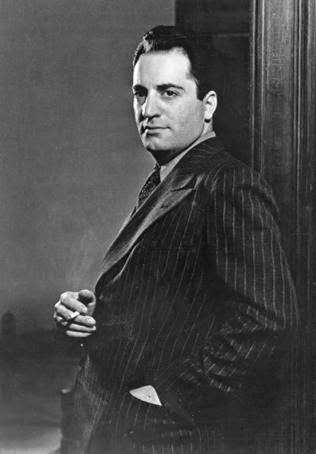

It was a time in the mid-1930s. The writer William Saroyan was driving from San Francisco to Los Angeles and, some miles down the road, decided he’d like to visit John Steinbeck in Pacific Grove. So he detoured. Steinbeck was busy writing but broke off to sit and talk with his fellow Californian.

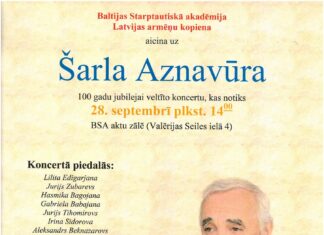

Neither could know the coincidence and irony of what was coming. In 1940, both men would win the Pulitzer Prize: Steinbeck in literature for The Grapes of Wrath, Saroyan in drama for The Time of Your Life, an alarmingly original treatment of people waiting for something to happen, and a harbinger of plays like “Waiting for Godot” — except that in Saroyan’s piece something dramatic finally does happen. Really, what were the odds of a couple of guys sitting in a little room in Pacific Grove, each simultaneously nabbing a Pulitzer a few years later — though Saroyan would turn his Pulitzer down, saying he did not believe in awards in the arts. Steinbeck would be quoted as saying, “Bill knows what he wants to do and I don’t see that it is anybody’s business.” He said he felt better about his Pulitzer because Saroyan, though rejecting it, got one too.

Of course Steinbeck had already shown what he could do, having written Tortilla Flat, his first popular novel — along with the stories later collected in The Long Valley — and likely at work on his 1937 hit, Of Mice and Men. When they met, however, Saroyan was simply the hottest short story author in America, closely identified with California’s Central Valley and the Armenian community around Fresno, much as Steinbeck came to be with the Salinas Valley and the characters around Monterey County. Known for writing quickly, Saroyan believed in spontaneity — which produced frequent masterpieces but also, now and then, a story that might need more work. But Saroyan was Saroyan, and The Time of Your Life, The Human Comedy, and The Daring Young Man on the Flying Trapeze would make him famous.

Back in Pacific Grove, Steinbeck said he’d like Saroyan to meet Bruce and Jean Ariss, who lived nearby. Bruce was an artist and Jean was a writer whose novel, The Shattered Glass, was inspired in part by the Monterey of the 1930s and 1940s. Saroyan followed Steinbeck in his car to the young couple’s home, and the evening went well, with plenty of wine and lots of talk. Recalling the evening some years later, Jean said that eventually Steinbeck decided he had to go home and get back to writing. Jean and Bruce invited Saroyan to stay for more talk and another glass, and they mentioned that they had become involved with a local literary magazine. Saroyan found that interesting and asked for more information.