DRESDEN — A picture is worth a thousand words. The saying has become a cliché, and for good reason: it holds true. Nothing could prove this more convincingly than an exhibition that opened on June 16 in Dresden, Germany. Organized by the “Haytun” Armenian Cultural Association in Dresden together with the Armenian Information and Documentation Center (IZDA, Berlin), the vernissage took place in the Martin Luther Church.

Introduced by Prof. Tessa Hofmann of the IZDA, who spoke via video link, it is not a new collection. In fact, it was first presented to the public in 1999, and since then has been displayed in several venues both in Germany and abroad, among them, the German Sinti and Roma Documentation Center in Heidelberg, the Progressive Synagogue in the London districts of Harrow and Wembley, the Peace Church in Bremen and the St. Catherine’s Church in Frankfurt, the Leer town hall in East Friesland and Anti-War Museum in Berlin-Wedding. This new version appearing in Dresden represents an important contribution to the continuing campaign to educate the German public, especially its younger generation, on the history of the genocide against the Armenians and other Christian minorities in the Ottoman Empire.

The exhibition is entitled, “Deportation, Persecution, Annihilation.” Father Eckehard Möller of the Dresden-Neustadt parish greeted guests and told them how he had first become acquainted with the Armenian question and the genocide. It was during a visit to Jerusalem that he received a leaflet from someone on the street. The leaflet showed a map of the genocide, with deportations routes and sites of massacres. It was a map that would lead him to learn about the events of over a century ago. The chairman of the Haytun cultural group, founded just a year ago, said a few words about the open wound which cannot heal, due to continued denial of the genocide, and expressed the hope that both communities here in Germany might find the way to work through the past and approach reconciliation, without political pressure from the current Turkish government.

World War I and the Camera

The items on display come largely from a collection of the Armenian Information and Documentation Center, which covers the genocide as well as Armenian life and culture in the period prior to the catastrophe. Hofmann summarized the historical process leading to the genocide perpetrated by the Young Turk regime, in the course of the World War and thereafter, a process that saw the collapse of the Ottoman as well as the Russian and Hapsburg empires. Clearly, she explained, it was impossible to record on film the complete unfolding of the genocide through slave labor, massacres and deportations, for many reasons; “to be sure the First World War marked the birth of photographic war reportage and the use of photos for propaganda purposes…. But the medium remained limited,” as cameras at that time were extremely costly, not easily transportable items. “Above all, those committing genocide certainly don’t want to be photographed while committing mass murder.” Legal prohibition by the Turkish authorities as well as fear of epidemic disease such as typhus prevented photographers from documenting the atrocities.

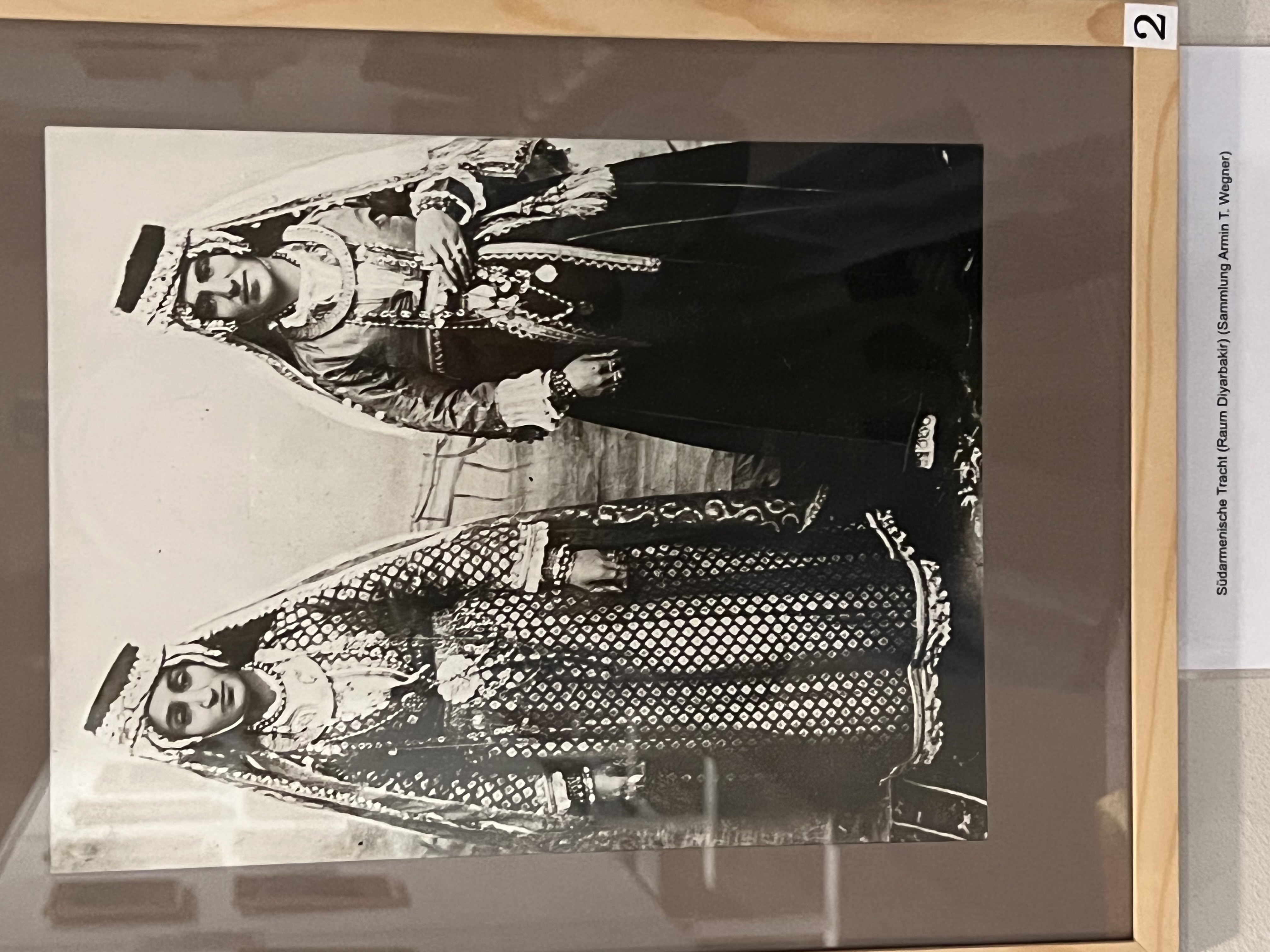

One exception was the work of German medical orderly Dr. Armin T. Wegner, who managed to take pictures of concentration camps near Aleppo, in the company of Swiss missionary nurse Beatrice Rohner; another was Danish missionary Karen Jeppe, who photographed the remains of starved victims in Urfa.