SALEM, Mass. — Armenians feel close to Ethiopia and Ethiopians due to centuries of relations as well as the fact that Ethiopian Christians share the same theology as the Armenian Church. Some wonder about superficial similarities between the Ethiopic and Armenian alphabets. Yet most Armenians do not know much about Ethiopian culture or history. There is a wonderful exhibit which can help remedy this. “Ethiopia at the Crossroads,” which premiered at the Walters Art Gallery in Baltimore last December (see Nora Hamerman’s “Armenian and Ethiopian Art Share Spotlight in Baltimore Exhibit” in the Mirror-Spectator this January), is now at the Peabody Essex Museum (PEM) in Salem, Massachusetts till July (and then will move to the Toledo Art Museum in Ohio from August to November).

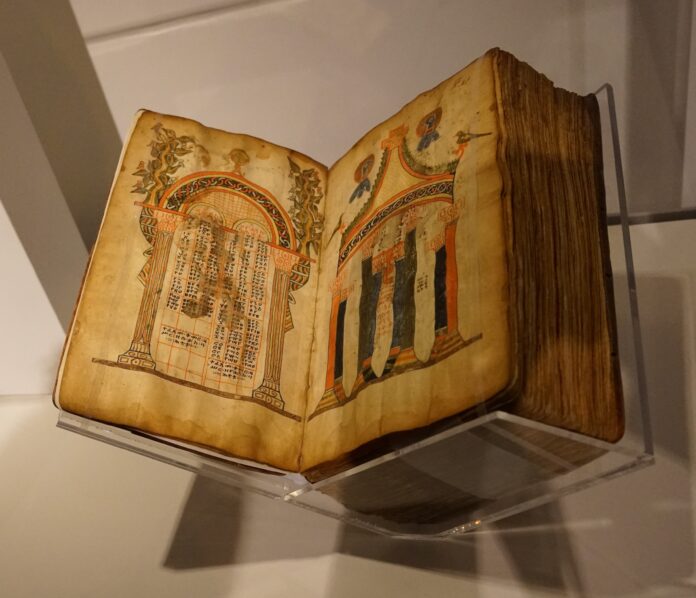

This exhibition places almost two millennia of Ethiopian art in a global context and even includes a number of Armenian illuminated manuscripts and artifacts among the approximately 200 icons, manuscripts, coins, crosses, metal works, carvings, textiles, contemporary artworks and videos on display.

Opening

At the opening of the exhibit for museum members on Friday, April 12, Petra Slinkard, Director of Curatorial Affairs and the Nancy B. Putnam Curator of Fashion and Textiles, noted that PEM co-organized this traveling exhibit together with the Walters and the Toledo Art Museum. She pointed out that an estimated 12,000 Ethiopians live in the greater Boston area, making it an important diasporan center, though the Washington D.C. and Baltimore area holds the largest concentration of Ethiopians in the US.

PEM exhibit co-curator Karen Kramer (also Stuart W. and Elizabeth F. Pratt Curator of Native American and Oceanic Art and Culture) spoke of the long rich Ethiopian heritage. Ethiopia was the only African nation to resist colonization and maintain its independence (along with Liberia). While global influences are visible, a distinct aesthetic emerged that belongs to Ethiopia alone, Kramer said. The African art collection of the Peabody Essex Museum was one of the first of its kind to be founded in the US, and includes rare and important Ethiopian icons, processional crosses, baskets and textiles. Many of these items, along with artworks from the two other co-organizing museums as well as loans from various American, European and Ethiopian lenders form the current exhibition.

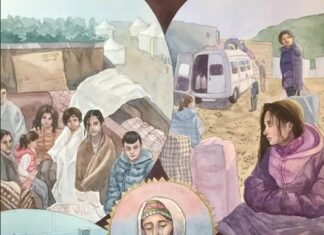

Lydia Peabody, co-curator of the exhibit and curator-at-large at PEM, spoke about the contemporary works in the collection by artists from Ethiopia, including a photograph from Aïda Muluneh, the first Black woman to co-curate the Nobel Peace Prize exhibition in 2019, and the next year to be commissioned for the Nobel Peace Prize exhibition herself. Kramer and Peabody acquired six of Muluneh’s photographs simultaneous with the preparation of the exhibition.