By Nora Hamerman

Special to the Mirror-Spectator

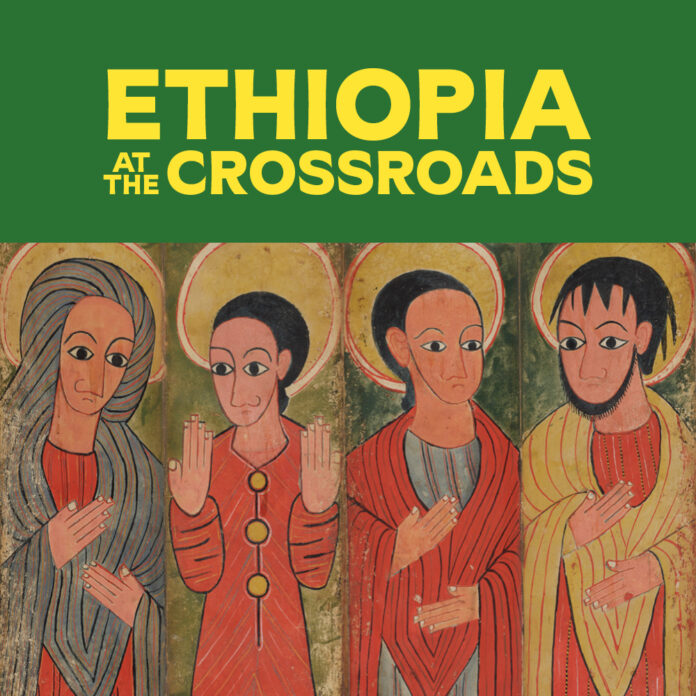

BALTIMORE — A new exhibit at Baltimore’s Walters Art Museum, titled “Ethiopia at the Crossroads,” is not only a delight for the eye and mind, but it also sheds light on a little-known relationship between the two oldest nations to have embraced Christianity, some 1,700 years ago. The show, which will also travel to the Peabody-Essex Museum in Salem, Mass. and the Toledo Art Museum in Ohio, reveals that Armenia and Ethiopia enjoyed close ties over the centuries that are visible in the two countries’ art.

One of the thrills of the Baltimore exhibit is a chance to see the Gospel decorated by Armenia’s most celebrated medieval book illuminator, Toros Roslin, who was active in the mid 1200s at the monastery of Hromkla, in Cilicia, now southern Turkey. This precious possession of the Walters Museum was not loaned to “Armenia!” — the exhibition at New York’s Metropolitan Museum five years ago — but now you can see it side by side with an Ethiopian Gospel book at the Walters show.

The Toros Roslin Gospel of 1262 (MS W.539) is not only the most lavishly decorated among the signed works of Roslin, but the only complete one in the United States. The manuscript was kept in the ancient trading hub of Sivas (Sepastia, formerly part of Armenia Minor, now Turkey) since the 17th century where it remained until the Armenian genocide in 1919. Ten years later it was purchased by American rail magnate Henry Walters in Paris. Walters, founder of the Walters Art Museum, had long been interested in Armenian art, but his passion was rekindled by the tragic events of the previous decade.

In the first gallery of the exhibit, titled “Ethiopia at the Crossroads” (the name invokes Ethiopia’s unique geographical position between Africa, Asia and Europe) there is a modern painting by Skunder Boghossian, an Ethiopian-Armenian painter and art teacher who worked mainly in the United States and was one of the first Black artists from the African continent to gain international attention and acclaim.