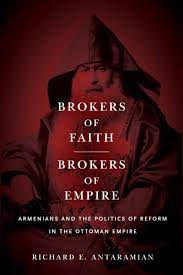

LOS ANGELES — Richard Antaramian’s 2020 book, Brokers of Faith, Brokers of Empire, breaks new ground in the historical analysis of the Armenian world of the late Ottoman Empire. In so doing, the book challenges assumptions long held in the Armenian community as well as in academia in regard to the development of Armenian nationalism and ultimately the interaction between Armenians and the Turkish state leading up to the Genocide of 1915.

Antaramian, who is a native of Wisconsin, did his graduate work at the University of Michigan–Ann Arbor, where he received his PhD in history in 2014. Under the tutelage of scholars such as Gerard Libaridian, Ronald Suny, Fatma Muge Goçek, and Kevork Bardakjian, Antaramian benefitted from the strong Armenian Studies program at Michigan. He is currently an assistant professor of history at the University of Southern California.

The book’s title is a reference to the powerful Armenian clergy whose role in the 19th-century Ottoman Empire was not only religious, but also political, economic, and social. Students of Middle Eastern and Armenian history are familiar with the idea that the Ottoman Empire operated on the “millet system,” whereby Christians and Jews were partially exempted from the Islamic laws of the Empire and allowed to operate under their own socio-political systems headed by their own clerical hierarchies. Eastern Orthodox believers were part of the “Rum Millet” (Byzantine “Roman” nation) under their patriarch while Armenians as the “Ermeni Millet” (Armenian Nation) were answerable to the Armenian Patriarch of Istanbul, who was answerable to the Sultan. Jews had their own structures and as Armenian Catholics and Protestants became separate denominations, so did they.

Armenian nationalist thought has generally referred to this system with phrases like “in the absence of political sovereignty, the Church kept the Nation united,” and has considered that the Armenian intellectual renaissance of the second half of the 19th century included a reawakening of national sentiment among this far-flung group united only by their church and language. Meanwhile, non-Armenian modern historians have seen the Armenians as an ethno-religious group who developed a concept of nationalism in the 19th century in rebellion against the Ottoman and Russian Empires, just as the Greeks and other Balkan peoples did. This follows the modern doctrine, originated in Benedict Anderson’s 1983 work Imagined Communities, that the idea of a “nation” was a social construct that was largely an outgrowth of the French Revolution. What all historians seem to agree on is that leading Armenians dedicated to reform in 19th century Ottoman Turkey, including Mgrdich Khrimian (Khrimian Hayrig) and others, were early Armenian nationalists and possibly pushing for Armenian independence. Antaramian’s research counters that seemingly obvious narrative. It also serves as a corrective to those who continue to intimate that the Armenians “got what was coming to them” in the slaughters of 1895 and 1915 because of their rebellion against the Ottoman State.

The main thrust of Antaramian’s argument is that Armenian reformers in the 19th century, including clergy like Khrimian and laymen like Krikor Odian and other leading Armenians who framed the Armenian National Constitution, were actually pro-government. Antaramian challenges the center-periphery paradigm of much of Ottoman historiography by arguing that Ottoman Turkey prior to the Tanzimat (“Reorganization,” 1839-1876) period was a country that operated under “networked governance.” In simplified terms: backroom deals, violence by Kurdish tribal chiefs, bribes from Armenian moneylenders, and the relationships forged by power brokers like the Armenian clergy of the title were more influential than the rule of law. The Ottoman government attempted to break down this world and bring the empire more closely under the control of the central government in Constantinople. Armenian reformers aided in that effort, argues Antaramian.