YEREVAN / ALMATY — Eduard Kazarian is a Kazakhstani sculptor who creates works ranging in size from small to monumental.

Born in 1964 in Almaty, he graduated from the Almaty State Theater and Art Institute in 1991. Since 1992, he has held more than 60 personal exhibitions in Kazakhstan and abroad, participated in collective projects, art festivals, international art residences, acted as a member of the jury of Kazakhstani and international art competitions and curator of Eurasia Sculpture Biennale, Almaty Kinetic Art Festival, represented Kazakhstan in the international project Reviving Humanity Memorial.

Kazarian is Laureate of the first independent Tarlan prize in 2000 in the “New Name: Hope” nomination in the field of fine arts. In 2012 he was Laureate of the national award “Person of the Year” in the nomination “People’s Love and Creative Achievements.” In 2018, he founded the Kazarian Art Center art space. It was awarded a special prize by the Organizing Committee of the annual Eurasian award “Choice of the Year” in the nomination “For creative achievements, significant contribution to the development of the cultural environment, promotion of fine arts.” In 2019, Kazarian was awarded the medal of the Ministry of Culture of Kazakhstan for his contribution to the development of the country’s culture.

His works are in the collections of museums in Kazakhstan, France and Spain; they have been exhibited in the US, Israel, Poland, the Netherlands, Russia, Belgium, Great Britain.

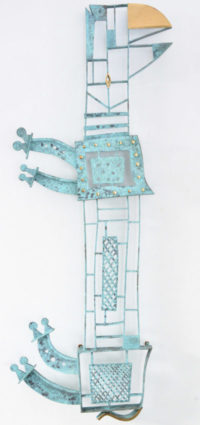

He works mainly with bronze, ceramics, steel. One of the main ideas of his work is reflections on the theme of the world, man, family, as well as the endless connection of all living things in nature.

Kazarian created a number of monumental works and public art projects in the urban and natural environment. He is also known for his tapestries, graphic sheets and jewelry. Kazarian considers exhibition activities to be a sphere that allows him to constantly experiment.