By Michael Bobelian

Republicans hit rock bottom in 1964. Lyndon Johnson crushed Barry Goldwater by a record vote margin, and after ceding 36 House seats, the GOP was outnumbered 2 to 1 in both chambers of Congress. Already humiliated by the electorate’s rebuke of Goldwater’s far-right ideology, his acolytes watched in horror as Senate Minority Leader Everett Dirksen and other GOP standard-bearers allied with liberals to enact civil rights legislation and Johnson’s Great Society agenda.

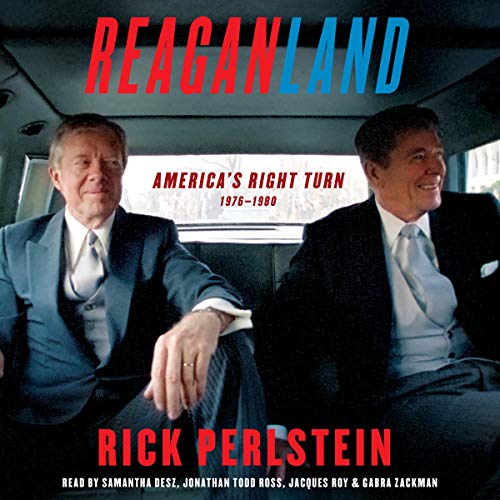

In three previous volumes, noted historian Rick Perlstein portrayed this epoch as the zenith of a liberal consensus and the origin of the conservative movement that came to dominate American politics. Starting in 1968, Republicans won eight of 13 presidential elections, controlled Congress for protracted intervals after spending most of the preceding four decades in the minority and appointed 15 of 19 Supreme Court justices. Published in 2001, Before the Storm recounted the rise of the firebrand Goldwater as the progenitor of this movement. Perlstein’s next two books, Nixonland and The Invisible Bridge, encompassed Richard Nixon’s presidency, followed by Ronald Reagan’s emergence as Goldwater’s heir. Reaganland: America’s Right Turn 1976-1980 concludes Perlstein’s authoritative and engaging series with Reagan capturing the White House.

Initially considered too conservative to win a national election, Reagan benefited from the electorate’s shift to the right, the development of unrivaled grass-roots and fundraising networks, and the exploits of cutting-edge political operators.

Perhaps no group personified these developments better than the New Right. Described by one of its pioneers as “radicals working to overturn the present power structure,” these public relations experts and campaign strategists commonly operated without the GOP’s imprimatur. Brazenly exploiting legal loopholes and shattering norms to the chagrin of the party’s patricians, the New Right zeroed in on racial resentment and divisive social issues — abortion, gay rights and the Equal Rights Amendment — to stir voters’ emotions. “We organize discontent,” declared one of its leaders, Howard Phillips. Alarmist and ugly — one newsletter opposing homosexuals and gay rights vowed to “protect . . . children from their evil influence” — the strategy nevertheless corralled Reagan Democrats to the party.

As the New Right mastered these newfangled strategies, religious institutions and large businesses, which had intermittently dabbled in partisan politics in the 1960s, gelled into strongholds for the GOP. Led by Jerry Falwell’s Moral Majority, evangelicals abandoned Jimmy Carter over abortion and gay rights and, through the proliferation of Christian television stations and direct-mail operations, backed Reagan even though he, like Donald Trump, had been divorced and was not particularly devout. Wary of escalating environmental and consumer protection regulations, corporations — “boardroom Jacobins” in Perlstein’s lexicon — amped up their lobbying efforts to promote the GOP’s calls for deregulation and lower taxes.