BOSTON – When you enter an independent or assisted living home, you sometimes feel like you are entering a different realm, where time is slowed down or halted, and the past and present simultaneously exist. Somehow Bostonian filmmaker Shevaun Mizrahi captured this almost mystical feeling in her 82-minute documentary “Distant Constellation,” which is playing in New York, Boston and Chicago before a national release. Set in a retirement home in Istanbul, the film includes glimpses into the lives of a number of Armenian residents.

As the viewer slowly sinks into the film, he gradually pieces together where he finds himself. The colorful dialogue takes place in multiple languages, Turkish, Armenian, English and French, unified through the English subtitles, but none of the names of the characters are given, nor is the place identified directly.

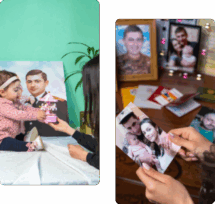

Among the main Armenians depicted, Osep Minasoğlu (Hovsep Minasyan, 1929-2013) is a famous photographer unable to take photos and constantly repeating phrases. Selma (a pseudonym) is an Armenian woman still living in fear, focused on her tragic family history and the destruction of her village in 1915. Like Osep, she passed away while the film was still being made, in 2012. Gaspar Beyleryan had been an Armenian priest but also had done a lot of metaphysical exploration. He is shown doing a hypnotism, and the film closes with the story he relates of a boy who drowns and dies, yet ends up living after all.]

Of course there are many quirky non-Armenian characters too. The elderly Levantine pianist Roger Dumas, for example, ends up attempting to charm and proposition the filmmaker, at least 40 years younger than him.

Filmmaker Mizrahi grew up in the United States but has close ties to Istanbul. She has an American mother who separated from her Turkish husband, so Shevaun would go to see her father and other relatives in Turkey during the summers. Consequently, she picked up some Turkish over the years. Her grandmother and other relatives there, being themselves part of a minority group there, spoke six or seven languages each, and her father grew up in the same area as the retirement home.

Mizhrahi said that she always was really involved with photography from an early age. A mentor in high school helped her build up a portfolio, and her worked was exhibited at the Smithsonian of American Art.