WATERTOWN — Violence toward women is more prevalent than thought in Armenia, and in the diaspora it is one of the unfortunate legacies inherited from Ottoman (Turkish) Armenia. On March 16, a large number of Boston-area Armenians came together in support of efforts to combat this violence through the Women’s Support Center (WSC) of Yerevan. Maro Matosian, founder and executive director of the WSC, was the main speaker at the event held at the Armenian American Social Club (Papken Suni Agoump).

Matosian, born in Romania, emigrated to the US in 1973, and studied art history. After living in a number of countries, she relocated to Armenia in 1991. There she worked nine years as country director of the Aznavour for Armenia Fund and, starting in 2006, another nine years as country director for the Tufenkian Foundation, while she established the WSC in 2010.

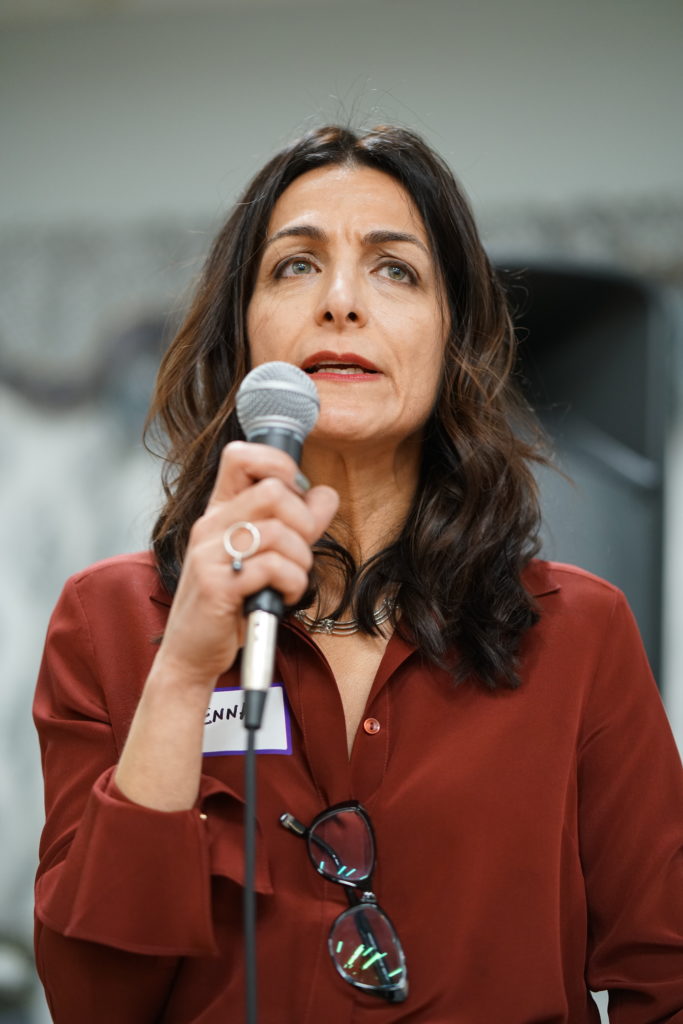

The fundraiser and informational evening was organized by three women in the Boston area, Lenna Garibian, Yelena Bisharyan and Martha Mensoian, under the name Friends of the WSC. Garibian, professionally a brand strategist who works as associate director of C Space, opened the evening. She related that visiting the center over the summer with her sister turned out to be a moving experience which convinced her to support it. She said she was impressed that “The staff has created an environment that is incredibly efficient, structured, well-run. It is clean, but it is also warm, loving and inclusive. It is an amazing place.” The staff there personally take risks in their work and is forced to operate secretly. Nonetheless, Garibian said, they were incredibly optimistic.

Garibian challenged the narrative that domestic violence activism destroys the fabric of society in Armenia. Instead, she stressed that society has to protect those who are most vulnerable. In her eyes, she said, Armenian society was behind the West by at least several decades since women in Armenia were facing conditions similar to those of women in the United States in the 1960s and 1970s. And, she said, despite all the progress in the United States, women here continue to face problems today in striving for their rights.

Garibian introduced Dr. Antranig Kasbarian, a lecturer, activist and Armenian Revolutionary Federation leader who used to be editor of the Armenian Weekly. With a doctorate in geography focused on Artsakh from Rutgers University, he joined the Tufenkian Foundation in 2003 and served as executive director until 2015. He continues to work at this foundation as a trustee and development of development. The Tufenkian Foundation was one of the organizational founders of WSC in 2010 together with the Armenian International Women’s Association (AIWA) and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). Kasbarian also happens to be Matosian’s husband.

Kasbarian remarked on the evolution of diasporan attitudes toward Armenia. Initially after independence, Armenia was seen, he said, as a “basket case” requiring emergency aid, but over time, more assistance programs work toward long-term rehabilitative and developmental assistance, helping people to help themselves. The diaspora, he said, has a lot more than money to give, and can be proactive in dealing with Armenia.