By Taleen Babayan

Special to the Mirror Spectator

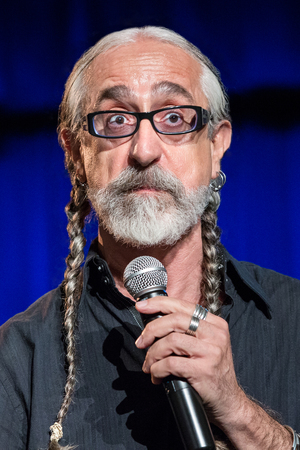

NEW YORK — It is a challenge to describe Vahe Berberian in one word: playwright, comedian, writer, painter, actor and director have all been used to depict this creative spirit, who has carved a niche in contemporary Armenian theater and art. His scope, however, stretches much further.

Berberian embraced his passion for the written word and the blank canvas from a young age in 1950s Beirut and further sharpened his ingenuity in Los Angeles over the last three decades, where he continues to create art on his own terms. Whether it is his plays, monologues, films, or paintings, his astute observances take center stage, as does his love for the Armenian language.

Entertaining with ease and smarts, Berberian is currently on tour with his sixth monologue, “Ooremn,” which he recently performed to great fanfare for the Greater New York Armenian community.