WATERTOWN — The Armenian Museum of America inaugurated its redesigned main floor introductory gallery, called “Armenia: Art, Culture, Eternity,” during an evening reception on November 15. President Michele Kolligian and Executive Director Jennifer Liston Munson presented their vision for the museum and thanked all those who participated in the renovation work. Despite the snowstorm, the building was packed. Watertown Town Councilor Lisa Feltner was among the guests.

Berj Chekijian, director of finance and building operations of the museum and formerly its executive director, introduced Kolligian, who spoke briefly of the history of the museum and its founding visionaries, led by the late museum board chairman Haig Der Manuelian.

The collection, started in 1971, was moved 30 years ago from the First Armenian Church in Belmont, Mass. to the present location, and, Kolligian said, a new phase in the life of the museum began eight years ago. Vice President Robert P. Khederian of the museum’s board had met Estrellita Karsh, widow of the famous photographer Yousuf Karsh. She was willing to donate photographic prints from original negatives of her husband’s work to the museum, but insisted on changes in the approach used for displays. To this end, she introduced Kolligian and others to Keith Crippen, director of design of the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA) in Boston, and to Jennifer Liston Munson.

Crippen recognized the possibilities in the former bank building, Kolligian related, and he and Munson began designing. Simultaneously, almost $1 million was raised by the Armenian Museum’s board, with Khederian playing an important role in this. The Karsh gallery opened in September 2011. Kolligian said, “We were completely changed from what we were before, and it was a very proud moment, and that was the beginning.”

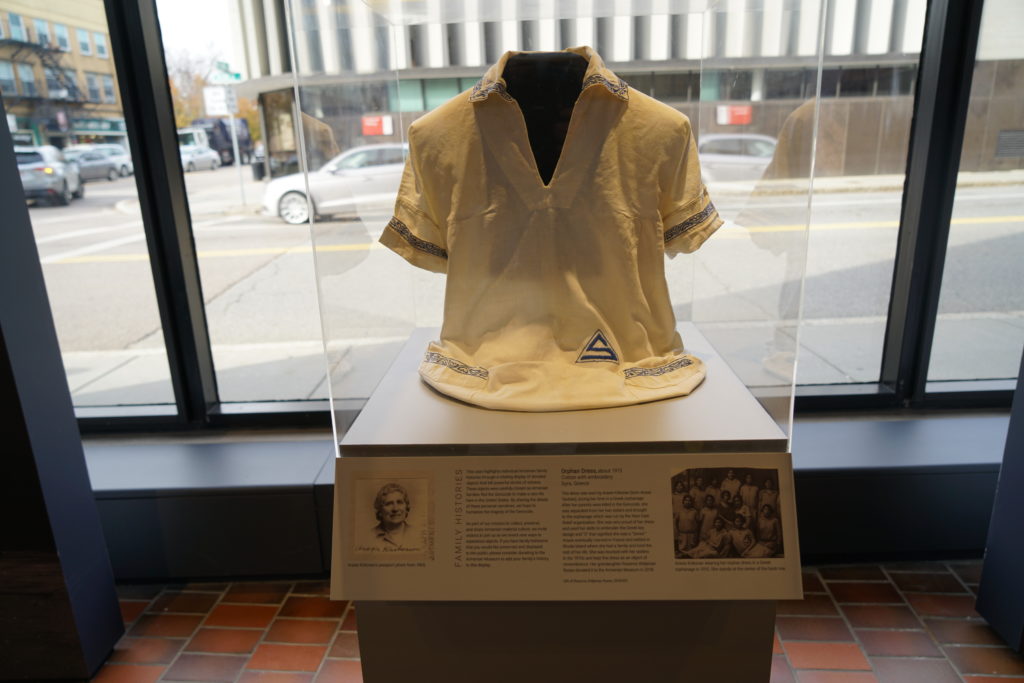

Initially Munson became part of the museum on a part-time but significant basis, designing the Simourian Family Galleries and the Adel and Haig Der Manuelian Contemporary Galleries. At the beginning of this year, she became the executive director of the museum.

Kolligian soon called Munson to the podium. Munson explained that the main goal of her work was to bring joy into the building together with Armenian culture. She said, “I think you might have noticed that the party starts at the street now,” referring to the ability to see vivid images and glimpses of the gallery from outside the museum. Munson continued: “We are beginning a new phase of sharing and connecting with the public and with ourselves, and it is pretty exciting.”