If recognition of the Armenian Genocide by a government and/or legislative body is to be more than a symbolic act, what follows it must be a broad effort to educate that nation’s population on what that genocide was.

When the German Bundestag (Parliament) took that step in June 2016, its resolution included explicit demands that the history of the Armenian Genocide be included in school curricula and teaching materials as part of at the process of “working through the history of ethnic conflicts in the 20th century…” Since education policy in Germany is the responsibility of the federal states, the resolution assigned them “an important role.”

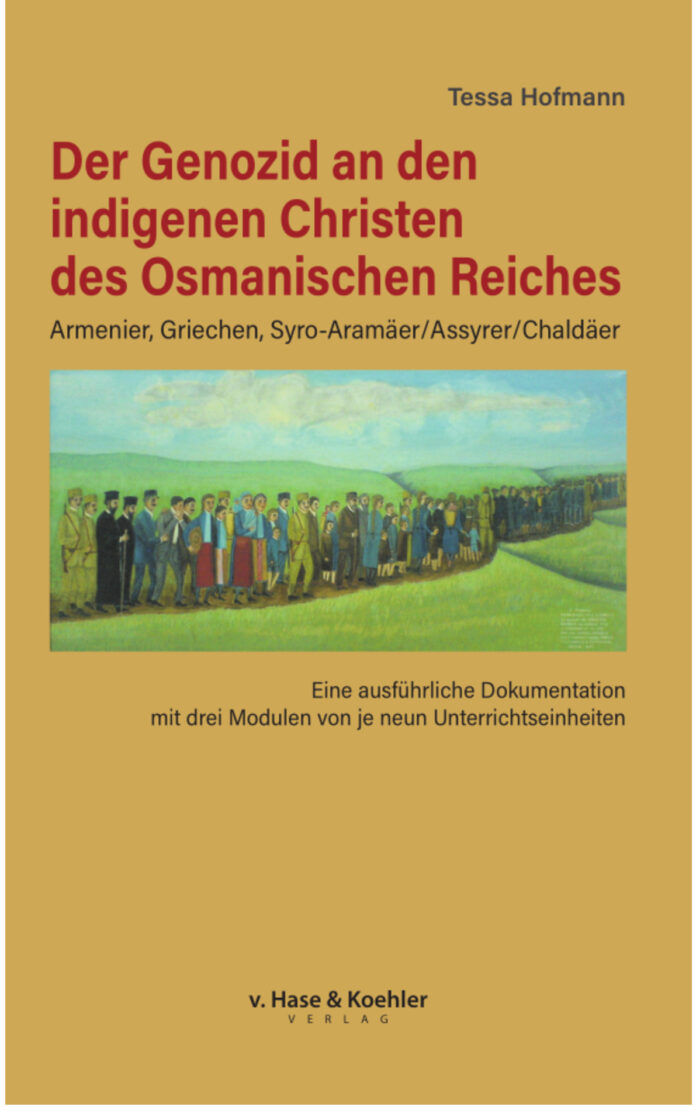

And yet, as Tessa Hofmann points out in the introduction to her new book, The Genocide of the Indigenous Christians in the Ottoman Empire (Hase & Koechler, 2024), little has been achieved: “Genocide education in cases other than the Shoah is offered in only six of the federal states, where it is optional; … in practice it hardly exists.” The reasons, as identified by pedagogue Martin Stupperich back in 2016, are that teachers lack the preparation and therefore the self-confidence to teach it, and adequate teaching aids, handouts as well as manuals, are simply not available. Those few materials that did exist, in two federal states (Brandenburg and Saxon-Anhalt) are either out of print or are limited in scope.

The new manual therefore fills an enormous, fundamental gap, quantitatively and qualitatively. Hofmann is a sociologist and researcher who has published widely on the subject, and has for decades been active in human rights efforts to recognize the genocide. As she explains, the volume treats all three victim groups, Armenians, Syrian Christians, and Ottoman Greeks, and provides an understanding of “the dangers of inter-ethnic as well as religious hate, thus serving as genocide prevention.” Furthermore, the manual addresses Germany’s special historical responsibility, not only as wartime ally of the Ottomans, but also as the home of a large number of immigrants from Turkey, not only ethnic Turks and Kurds, but also Armenians, Pontic Greeks, and Syrian Christians. “The dark chapters of Ottoman-Turkish-German history affects them as well,” she writes.

The new text, almost 400 pages long, is indeed a comprehensive manual, divided into two parts: documentation and modules for teachers and students. Part one, comprising six chapters, is historical documentation, covering the development of the concept of genocide, the role of Raphael Lemkin and the UN Genocide Convention, followed by “Geography as Destiny” for the three population groups, before dealing with the Ottoman Empire. This chapter lays out the role and status of Christians in the Ottoman Empire, the attempts at reform, population policy, the Balkan wars, Young Turk revolution, through the war.

The central and most thoroughly developed section, chapter four, follows the course of the genocide, from the first massacres throughout the war years and beyond, including the Treaty of Lausanne. All regions and populations groups are treated in detail, the fate of women and children, including child abduction and forced Islamization. Chapter five presents statistics on victims.