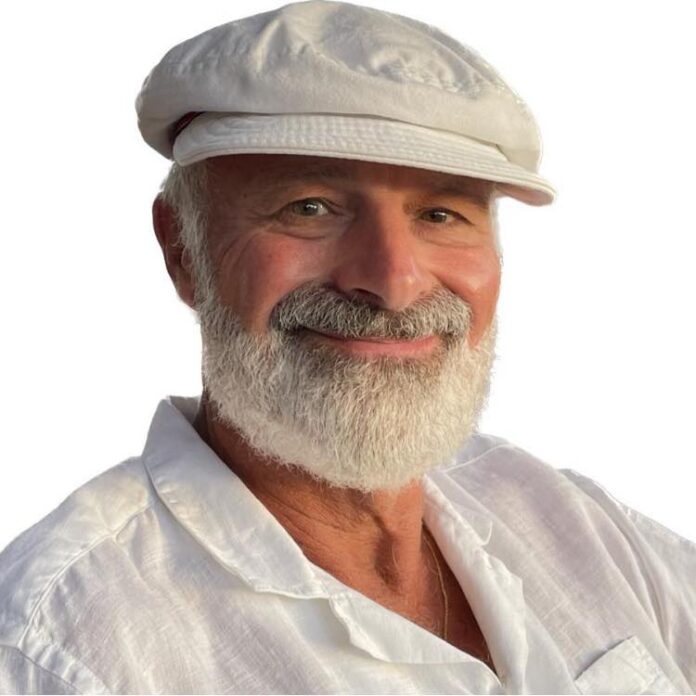

YEREVAN-MULHOUSE, France — Swiss-French writer Roland Godel (born in 1958, Geneva) has been working as a journalist for more than 15 years. In 1999, he joined the State of Geneva as head of communications and since then he has been writing stories and novels for young audiences. He received the 2008 Chronos Prize for The Little Secrets of the Mimosas Boarding House, as well as the 2010 Youth Historical Novel Prize and the 2010 Tatoulu Prize for The Witch of Porquerac. Other his novels are My Father’s Secret, The Meaning of Honor, The Last Stronghold, etc. In 2016 Godel received the UNICEF Children’s Literature Prize for I Dared to Say No!, recognizing its powerful message about standing up against harassment.

Roland Godel is father of two children, and lives between France and Greece.

Dear Roland, in your writings you explore various social issues and delve into human relationships, emotions, and feelings. Your literature is often aimed at young readers. Can this be explained by the fact that you have remained young at heart?

Yes, at 67, I try to stay young at heart, and imagining and writing novels for teenagers constantly brings me back to my own youth and personal experiences. It helps prevent me from becoming a bitter, disillusioned old man stuck in his certainties. I deeply believe that young adolescents have a wonderful ability to receive and absorb stories that move them with completely open minds, allowing themselves to fully feel the range of their emotions. This is how they question things, develop their critical thinking, and shape their identities. Later, after the age of 15 or 16, young readers begin to be constrained by prejudice, certainties, and defensive postures.

Your short children’s novel I Dared to Say No! focuses on bullying, a subject that is very close to me. Do you think this topic will always remain relevant, even though it seems that schools—particularly in the West—are trying to reduce it to a minimum?

It seems to me that this issue is more relevant than ever. Just look at the authoritarian, ruthless men who currently occupy the highest positions of political power—Trump, Putin, Netanyahu, Orbán… These are typical profiles of bullies and intimidators. They are men shaped by power dynamics, who seem to enjoy having control over others. Of course, if you look deeper into the psychology, you’ll often find that bullies are people who themselves suffered in childhood and whose lives are driven by a dark story of revenge. So, it’s a complex issue, and that’s precisely why we need to raise awareness among children at the earliest possible age—an age of openness.