It is difficult to think of a more appropriate title for a collection of photographs that document the everyday lives of the last three remaining employees of the Mt. Aragats Cosmic Ray Research Station located 3,300 meters (2 miles) above sea level on the slopes of Mount Aragats in Armenia, some 25 kilometers (15 miles) from the closest village. Two scientists and a cook tasked with maintaining the facility live in quasi-complete isolation in temperatures averaging -15 degrees Celsius (5 degrees Fahrenheit), with snow covering the ground two thirds of the year.

It took photographer Yulia Grigoryants six years and her participation in the VII Masterclass — an ambitious training program aimed at developing new talent in documentary photography — in 2018-2019 to complete Cosmic Solitude (printed in Italy by EBS, 2024), a project that attempts to bring to light “this unique station and its mission to serve humanity’s scientific endeavors.” The research data collected from the Station’s sensors and experimental laboratories contribute to the understanding of solar phenomena and their impact on the Earth’s atmosphere and the space environment. A landmark discovery was the observation, in 2005, of solar protons with the highest energies ever recorded. The sighting is considered a unique contribution to high-energy cosmic ray physics.

The Aragats Cosmic Ray Research Station was stablished in 1943 under Soviet rule — Joseph Stalin’s portrait still hangs on one of the walls — but has been largely neglected following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. A facility that at its height employed around one hundred scientists currently has three “devoted inhabitants” who work one-month shifts, with one month off, to maintain it twenty-four hours a day year-round. “Virtually abandoned” is how Grigoryants characterized the Station in her presentation at the Abril Bookstore Book Event at the Center for Armenian Arts in Glendale.

The artist divides her time between Armenia, her home country, and France where she has lived since 2017. As a child growing up in Armenia Grigoryants was plagued with a feeling of being an “outsider . . . often feeling lonely without many friends by my side.” (Grigoryants was born in Azerbaijan but she and her family fled to Armenia when she was only four to avoid the pogrom against the Armenian population in Baku).

“The weight of my solitude didn’t inflict immediate pain; rather, it became a familiar companion, a silent companion I grew accustomed to, a companion that silently bore witness to my unspoken yearning for connection,” she writes in “The Weight of The Solitude,” a short essay published alongside the seventy photographs assembled in the elegant volume.

In her early 20s, in Yerevan, Grigoryants started making frequent trips to the mountains, specifically to Mount Aragats, to find “solace among the peaks.” These trips fostered a “deep love for my country, my historical homeland,” she avers. Despite a comfortable life in France with her husband and two children, the artist “ache[s] for Armenia.” Her biggest fear is that her children “may never have as deep a connection with Armenia as I do.”

“In France, the yearning for connection sometimes screams within me. However, the abyss remains,” she confided.

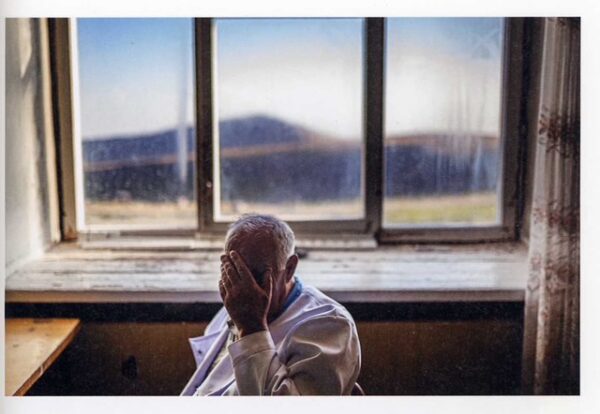

It is perhaps the need to penetrate this “abyss” that took Grigoryants to one of the world’s most remote scientific outposts whose isolated setting may evoke the feeling of isolation inherent in human existence. Acknowledging her own “unspoken yearning for connection,” “Loneliness is a common experience for many,” writes Grigoryants. Indeed, in an uncanny way, her shots of the deep blue skies and of the panoramic views of the expanses of snow surrounding the many “huts” of the station, with Mount Ararat looming in the distant background some ninety kilometers away in Turkey, capture the vast empty spaces within. The images of the interior of the station, on the other hand, of Artash Petrosyan, the cook, sitting at the kitchen table surrounded by his appliances and pots and pans, reminiscing the time when he used to cook for a hundred employees, or of Laboratory Assistant Karen Asatryan playing pool alone — or walking outside alone in deep thought with white snow all around — give us a revealing glimpse into the inhabitants’ “cosmic solitude.”

Grigoryants’ photographs invite much reflection. One wonders if Karen Asatryan, Edik Arshakyan and Artash Petrosyan have chosen the isolation of the station to escape the distractions of the external world so they can explore the “abyss” of their own inner worlds — “But I need solitude, which is to say, recovery, return to myself,” affirms famed philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche — or if theirs is a selfless ”mission to serve humanity’s scientific endeavors” in its efforts to create a better world. Clearly, the book highlights the importance of what the scientists do. What seduces the viewer, however, is the artist’s tremendous empathy for their situation. Grigoryan’s images that reach into the depths of their isolated lives reveal the desolation, perhaps even the fear, of working in an (inhumanly?) cold and remote setting, in laboratories that reach up to nine levels underground.

Notwithstanding, the three employees are not resigned to hopelessness. They return to their families in the nearby villages after their month-long shifts, only to come back “home.” “When you stay here so long, it becomes like a home,” says Lab Assistant Edik Arshakyan, whose grandparents and father also worked at the station. Karen Asatryan celebrates the freedom working at the station gives him: “I like the freedom that I have here . . . [even if] sometimes you are trapped here, especially in winter.”

The book gives no suggestion that the Research Station will end anytime soon. Indeed, Cosmic Solitude prompts the viewer to question a government that refuses to adequately fund a project that has made significant contributions to humanity’s efforts to understand its habitat. One can only hope that Grigoryants’s honest documentation will engage policy makers in discussions that may result in funding for the research facility. Her book is evidence of her faith in that possibility.

A new generation of women photographers is gaining visibility in an art form traditionally dominated by men — certainly not for lack of talented women. Anush Babajanyan, Diana Markosian, Armineh Johannes are only a few of the names that have been featured in the Armenian Press recently. These women use their art to engage social and political issues. Grigoryants’s work resonates on an even larger, a more profound level. Cosmic Solitude offers the viewer insights into the unseen aspects of the human experience. The many shots of the views from the large windows of the buildings of the Station evoke the “isolation and solitude” her project set out to explore.

Grigoryants received the Best New Talent Award at the International Photography Awards in 2016. Her work has been exhibited and published in major outlets internationally.

Cosmic Solitude is bilingual, with Anoush Ajemyan-Mkrtchian’s Armenian translations following the English originals of Grigoryants’s essays and detailed descriptions of the photographs. The book is available for purchase at Abrilbooks.com.