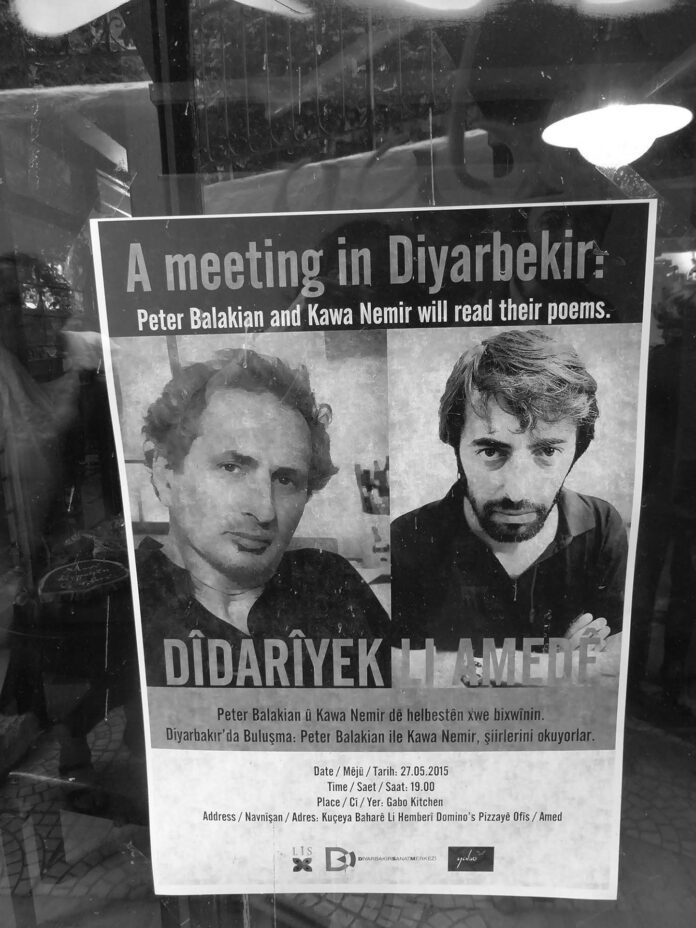

WATERTOWN — Peter Balakian, Pulitzer Prize winning author of eight books of poetry and four of prose, continues to explore the Armenian past and future. In May 2015 he went to Diyarbakir, Turkey, the Dikranagerd of the Armenians, to give a reading from his works. This was the city where his grandmother was born, and where her family was massacred in August 1915. This was an unusual visit; it fell in a small window of time where it was possible for an Armenian to speak in a public event there. The two sponsors of the event today remain either in prison (Osman Kavala) or exile (Kawa Nemir).

Balakian looked back at the significance of this event and his visit in an article published last fall, 2023, in AGNI magazine (no. 98), simply titled “A Poetry Reading in Diyarbakir.” Several paragraphs from the article are excerpted below, followed by some further thoughts by Balakian in response to questions from the Mirror-Spectator.

“I was too caught up in the euphoria of the moment to imagine that the two men who hosted my poetry reading in Diyarbakir would be in exile or prison two years later, and that the entire old quarter of the city would be destroyed only months after our departure. May 2015 was a spirited time to be in Diyarbakir, the Kurdish center of Turkey in the southeast. It was a moment of hope for democracy in Turkey and for Kurdish rights after decades of violence and suppression. My visit to Diyarbakir to give a reading with the Kurdish poet Kawa Nemir in the centennial year of the Armenian Genocide meant that I would read and discuss the story of my family’s mass murder and expulsion from their historic homeland. A few years earlier such an idea would have been absurd, especially given the laws and taboos in Turkey. And the 2007 assassination of Armenian human rights activist and journalist Hrant Dink midday in downtown Istanbul still hovered. But that spring, traveling with my family on a pilgrimage to historic Armenia in eastern Turkey, I felt hopeful about the new winds of democracy.

“There was a cultural revolution happening here — in a country where in the first years of the twenty-first century it was still illegal to use the word Kurdish in public; where Kurdish dress, schools, and radio had been outlawed. There were fifteen million Kurds, a quarter of the population of Turkey, the largest ethnic minority in the country and the largest stateless ethnic group in the world, and they were forced by law to call themselves “mountain Turks.” As a result of decades of Kurdish civil rights struggle, some liberalizing forces in Turkey, and pressure from Europe in the wake of Turkey’s then-hoped-for admission to the EU, President Recep Erdogan and his government assented to legalizing the Kurdish language, radio, and traditional dress. But amid this new energy in the streets — the Turkish state was ubiquitous. Army jeeps, soldiers with automatic rifles, police on street corners. And the green metal fence of the military base just a few yards from our hotel driveway seemed to stretch for miles. In this tinderbox, the Kurds that we met greeted us with a mix of delight and desperation, as if to say, Glad to see you — and don’t leave us here alone.

….

“In the hotel lobby, the poet Kawa Nemir sat waiting for me. A hip-looking guy around forty with a dark beard and thick black hair, he had mentioned the day before that he’d translated a couple of dozen British and American poets into Kurdish. I thought he meant a couple of dozen poems. But from his satchel he pulled a stack of bilingual editions of his Kurdish translations of Emily Dickinson, Walt Whitman, T. S. Eliot, W. B. Yeats, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Stephen Crane, Sara Teasdale, Shakespeare’s sonnets, and more. I felt buoyed up by Nemir’s books, his knowledge, his immersion in poetry. Finding a fellow poet 8,000 miles from home reminded me that the fellowship of literature is universal. Nemir put the books in my hands. ‘Please, they’re for you.’