OSHKOSH, Wis. — Richard Kalinoski is not Armenian, yet three of his works — including the most famous — deal with tragic chapters of Armenian history.

“I’m proud of each one of them,” he said in a recent interview.

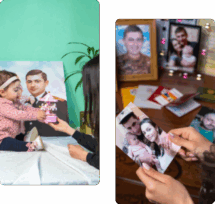

One, the multi-award-winning “Beast on the Moon,” written and performed hundreds of times since 1995, has been translated into more than a dozen languages. It deals with the aftermath of the Armenian Genocide, when many young women became picture brides and married men they had not set eyes on in the US or Europe.

A subsequent play, “My Genius of Humanity,” regards the nergakht, or repatriation of the 1930s and 1940s, when Soviet Armenia presented itself as heaven on earth for Diasporan Armenians. Thousands of Armenians from all over the world flocked to Soviet Armenia, only to be regarded with suspicion, have their money confiscated or even exiled to Siberia to work in gulags.

The play just finished an acclaimed production in Oshkosh.

Just Write