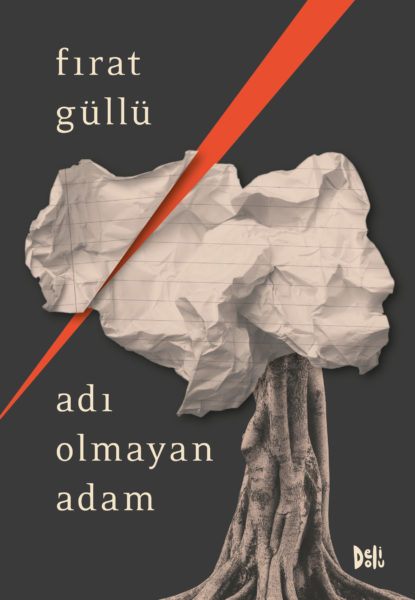

YEREVAN / ISTANBUL — Fırat Güllü is a Turkish historian, writer, translator and theater historian. He has a Bachelor’s degree in History and a Master’s degree from the Atatürk Institute for Modern Turkish History at Boğaziçi University. He has carried out acting, instructing, and directing responsibilities within Boğaziçi University Players for years, as well as acted in various productions at Theater Bosphorus. His various translations and writings were published in “Mimesis – The Translation and Research Periodical of Theater.” Fırat is a member of the Bosphorus Performing Arts Ensemble and of the Editorial Board of “Mimesis.” He published his works on Ottoman performing art history named “Vartovyan Theatre Company and the Young Ottomans” in 2008 and “System Crisis and Theater in the Ottoman Empire” in 2017. Fırat Güllü translated Kevork Bardakjian’s PhD thesis named “Hagop Baronian’s Political and Social Satire” into Turkish together with Zeynep Okan (from English into Turkish). Finally, this year, he published a novel called “The Man Without a Name,” inspired by the life of Istanbul-based Armenian playwright Arman Vartanyan (1930-2015). Fırat is a member of the History Foundation and of the Editorial Board of its periodical “Toplumsal Tarih” (Social History) and works as a history teacher in a private high school.

Fırat, we met in 2013 in Venice, where you were part of Summer Course of Armenian Language and Culture. Where are your Armenian interests come from?

Sometimes they ask if I am the grandson of the famous Armenian theater director Güllü Agop (Hagop Vartovyan) because of my surname, but it couldn’t be possible for me to truly discover this important figure of our cultural history till I started working on theater history. I knew very little about the great contribution made by famous Armenian actors and actresses to the modernization of Turkish theatre. In fact, I did not have the opportunity to focus on the subject until 2007. Hrant Dink’s assassination in that cursed year pushed every conscientious citizen of the Republic to a serious confrontation with the official nationalist history. This sad historical turning point caused me to completely change my works’ direction and I started to work on Armenian theater in the Ottoman and Republican eras.

Turkish theater specialist Metin And wrote that how much we thank the Armenians for their contribution to Turkish theater, will not be enough. Yet about this contribution only narrow circle of specialists know.

Especially in his first works in the 1960s and 1970s, Metin And tended to consider the development of modern theater in Turkey from a multicultural point of view. It was a pioneering effort in the academy, which usually had a rather nationalistic structure. However, after the military coup of September 12, 1980, because of the witch-hunt against left-leaning intellectuals, his approach to his earlier works began to change. The epilogue to the new edition of his important monography about Hagop Vartovyan named “The Ottoman Theater” (firstly published in 1960s and then in 1990) is a clear indication of his changing attitude to the issue. I took this topic into consideration in my work titled “Vartovyan Theater Company and Young Ottomans.”