CLEVELAND — Cleveland’s annual Armenian Festival was hosted by St. Gregory of Narek Armenian Church in Richmond Heights, Ohio on September 17 and 18. The festival, in its 20th year, brought together Armenians and non-Armenians from the local area and throughout the state of Ohio for food and music in the spacious grassy field between St. Gregory of Narek’s church and cultural hall.

The Cleveland community is small but very energetic. The local Armenians come from all parts of the world, all backgrounds, and all walks of life. Young people from Los Angeles or Boston who arrived recently to attend school rub elbows with grandparents who immigrated from the Middle East 40 years ago; American-born grandchildren of the Malatiatsi Genocide survivors who founded the community a hundred years ago work together with relative newcomers from Yerevan and Baku; and everyone seems to get along.

The small size of the community and the friendly Midwestern values have enabled various groups of immigrants to bridge their divides. “We don’t care about those divisions — we are welcoming,” says Parish Council chairwoman Mona Karoghlanian, who organized the Festival along with the rest of her committee.

Karoghlanian is practically the one-woman foundation of the Cleveland community. Having served as chair for many years, it is her family legacy and clearly her passion. (She is also a Diocesan Council member.) Born in Cleveland, her grandparents were immigrants from Malatia, like many of the early settlers, and staunch ADL members. “I was telling our [municipal] councilwoman, after the Turkish massacre it was our community’s dream to build a church here. And it took selling red Easter Eggs door to door, but we finally built the church in 1962.” While much of the population today has recently arrived from Armenia, the families that built the church are still the central organizers of much of what goes on, though the relative newcomers seem eager to volunteer and take on new responsibilities.

Even though Karoghlanian grew up attending ADL conventions with her grandfather and joined the organization herself, partisan divides are less important than keeping the Armenians together. “Those divisions don’t matter as much anymore,” says Serop Demirjian, a native of Sasoun, father, grandfather, and deacon of the church. An Antelias-based group in town used to rent space and hold services and events, but they eventually gave up and now everyone in the area goes to St. Gregory. The folks in Cleveland seem to want to avoid the political infighting and bureaucratic nature of Armenian institutions. They run things their way, with little interference from the fast-paced and divisive outside world of the East Coast, Detroit, Chicago and California.

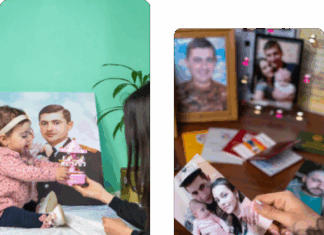

Festival Brings All Together