ԼINCOLN, R.I. — As we pulled up to the well-kept, unassuming 1950s-style ranch, my driver announced: “this is the House that George built.” Getting out of the car, I stared up at the home, which was as well-constructed as one could hope, but did show the marks of a personal design. “You built this yourself?” I asked. “Well, I had someone do the brickwork,” George replied. Nobody’s perfect, I suppose.

George Chakoian is 97 years old and still lives with his wife of more than 70 years, Mary, in the house he built in here. Down the street is a house his younger brother Jack once lived in before moving to North Providence. Jack passed away earlier this year at age 95. By now you have realized that 97-year-old George was the driver in the first sentence. I was supposed to meet with George to interview him, but when I asked for directions to his home, he insisted on picking me up.

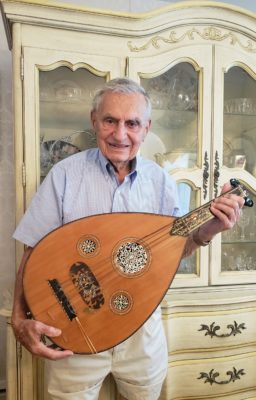

George is one of the last of a breed of Armenians from the first generation born in America, who embody what was great about the Greatest Generation. His late brother Jack could have been described in the same manner. Both were WWII veterans; George served in the Air Force in World War II and worked for the government as an aerospace engineer for over 50 years after graduating from the Rhode Island School of Design. He and Mary live by themselves with no assistance, and their home is the picture of the American Dream. Military ribbons, pictures with Rhode Island Senator Jack Reed, and a Gontag from the Catholicos of All Armenians adorn the walls of the family room; an award recognizing Chakoian as an inductee of the Rhode Island Aviation Hall of Fame sits in the dining room under wedding pictures of his daughters; a baby grand piano and an oud can be found in the living room, the 1950s décor of which is in impossibly pristine condition. And he still drives.

When I visited Providence two years ago, George’s brother, Jack, 93 at the time, also insisted on driving. Jack Chakoian was an interior decorator for some 50 years and owned his own business, RI Decorators in Cranston. Aside from being a successful businessman, Jack was a fixture at Sts. Sahag and Mesrob Church in Providence, attending every function and Armenian Church Youth Organization of America (ACYOA) dance (often leading the line even in his 90s), showing up to Divine Liturgy every Sunday, and acting as a general pillar of the community.

A self-described “gym rat,” Jack was known for staying in excellent shape his entire life — one of the more popular stories about him was how he would play basketball with ACYOA members who were in their 20s when he was well into his 50s, and more than keep up.

A World War II veteran like his brother, Jack had served his time in the Navy, and was honored at the North Providence Town Hall in 2014, where he spoke as the Armenian flag was raised in honor of the 99th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide. Jack spoke about his parents’ survival story as well as growing up in the early Armenian-American community, which can be viewed here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vlYsOzmh2lM&t=1s