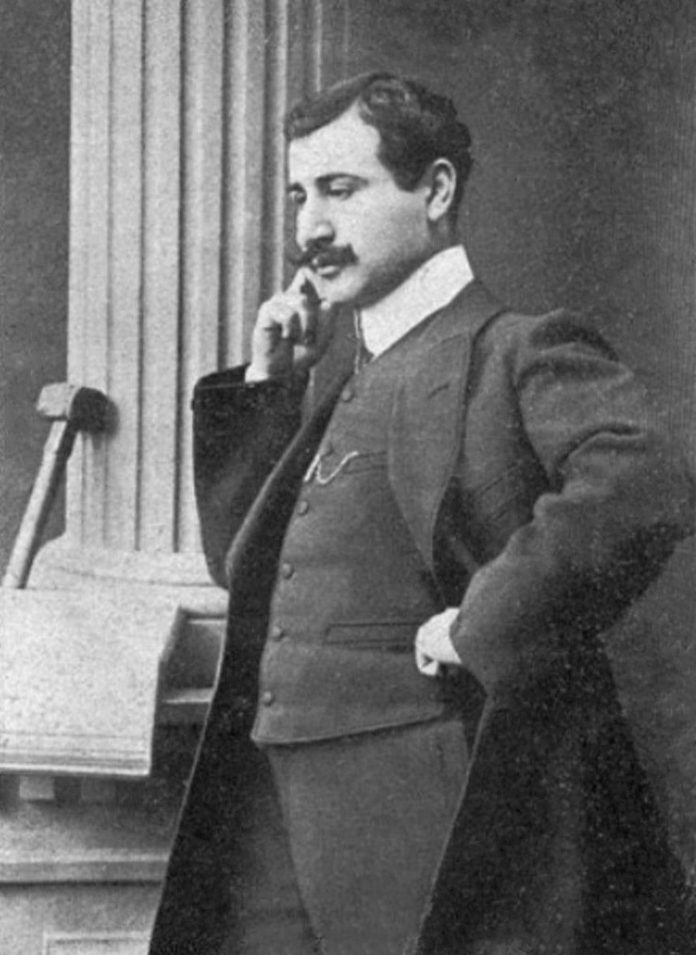

Daniel Varoujan [Taniel Varuzhan] led a short and tragic life. Born into poverty in 1884 in the Prknig village of Sepasdia (Sivas), Varoujan studied at Venice’s Mourad-Rafaelian School before obtaining a scholarship to attend the University of Ghent in Belgium from 1905 to 1909. These were lonely but enlightening years for a young man so far away from his native soil. Five years later in 1914 in Constantinople he would found the group “Mehian” along with fellow writers Gosdan Zarian, Hagop Oshagan, and Aharon and Kegham Parseghian. The group’s name, “temple” in Armenian, referred back to the ancient Armenian pagan gods. In 1915 Varoujan was deported towards Chankiri and gruesomely tortured to death by the Young Turks.

A recent 2019 special issue of Revue Belge de Philologie et d’Histoire [The Belgian Review of Philology and History] sheds important light on the details of Varoujan’s stay in Ghent. It may be the definitive study on the poet’s life during this period. The seven pieces presented here range from anthropological and factual accounts (van Nuffelen and Payaslian, de Messemaeker and Verbruggen) to literary and theoretical ones (Beledian, Nichanian). Some are eloquent and deft, others rather dry and formal. Together they form a fascinating look at the great poet’s life and psyche during the period examined, as well as to the city of Ghent as a whole.

Varoujan in Ghent was a busy if sometimes desperate young man: he spent long days and nights studying and writing brilliant verse, became an ally of the socialist party, and implored various Armenian organizations abroad to subsidize his tuition and coursework. He took up the cause of working-class factory workers and deplored the supercilious indifference of the upper classes whose members became rich off the labor of others. At first he could not speak any of the local languages — Flemish or French — and was taken aback by the comparatively cold temperament of his hosts.

From Peter van Nuffelen and Simon Payaslian‘s introductory essay, “An Armenian Poet in Ghent-One Hundred Years Later,” we learn that Varoujan was already experimenting and pushing back boundaries, including classic forms of meter and rhythm: “Varoujan rejected the strict adherence to the modes of versification that existed at the time in Armenian poetry. According to him, poetry was the medium through which nature took form and gave expression to the authenticity of (human) thought.” (P. 782, translation mine)

In this introductory essay, the authors discuss the relationship between Belgium and the Ottoman Empire and point to the fact that for Varoujan and his compatriots, Europe remained the cultural example to be emulated. This piece is complemented by Pieter de Messemaeker and Christophe Verbruggen’s “Foreign Students at Ghent University Around 1900.” The latter provides a comparative study on the countries of origin of foreign students in Ghent. It also examines why they found the city an attractive destination for their studies and how they in turn contributed to its intellectual and economic development.

In a sometimes maddening but fairly accurate historical rendering of the treatment of Ottoman Armenians and the founding of a short-lived Armenophile movement in Belgium, Houssine Alloul and Henk de Smaele (“Armenia in the Imagination and Politics of Prewar Belgium”) examine the success of Armenians — or “Oriental Christians” as they were sometimes referred to — in the Turkish empire. They quite correctly allude to the economic jealousy that this success engendered and to the clash between Christendom and Islam. While it is certainly true that depictions of Islam (read: Turks) as “barbaric” by the Belgians were racially biased, the authors at some points come off as apologists for the horrific acts committed by the Ottoman government under Abdul Hamid in 1894-96 and the Young Turks in 1915-1923.