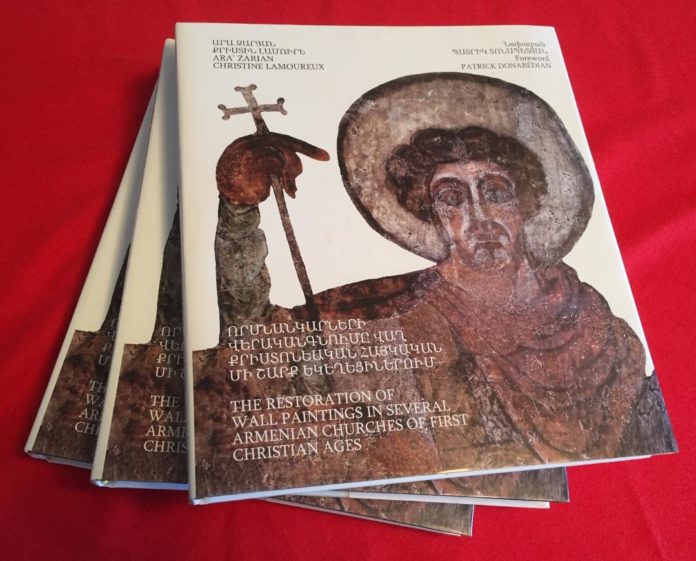

YEREVAN – The Armenian and English-language book The Restoration of Wall Paintings in Several Armenian Churches of First Christian Ages is the result of an eight-year research, study and restoration campaign of frescoed cycles, carried out in various early Christian churches located on the slopes of the mythical Aragatz Mountain. The authors have repeatedly traveled to Armenia, engaging passion, devotion, means and professionalism to recover, preserve and restore wall paintings of extraordinary beauty and historical-cultural value. Their goal is to maintain and transmit the immense load of messages, not always very clear, coming from the depths of the centuries, never studied in depth and systematic so far.

This 330-page work recently published by Tigran Metz Publishing House in Yerevan contains 703 color photos and pays homage to the pioneer of the field, the Russian scientist Lidia Dournovo, who in the 1950s and 1960s had made reproductions of many frescoes now deposited in the National Art Gallery of Armenia. For more information or to order the book, email arazarian@gmail.com.

The following is a slightly abridged version of Patrick Donabédian’s foreword to this book.

In the history of medieval Armenian art, wall painting is one of the least studied and most problematic spheres. Here are some reasons for this situation: the small number of surviving fragments and their poor condition, the complexity of the historical-religious basis, the almost complete destruction of the heritage in the historical western part of the country, and, in the case of miraculously preserved fragments, their inaccessibility to field work. This is why there is still no more-or-less comprehensive view and research about early Christian and medieval Armenian wall painting art. Our knowledge is especially limited in the field of artistic decorations of seventh-century monuments, although some information is available from N. Kotanjyan’s book Monumental Painting of Early Medieval Armenia (Yerevan, 2017). Meanwhile, in that era, there were very favourable conditions for the spread of wall-painting art. Here are the main two ones:

- Beginning in the late sixth century, and particularly during the period between the late 620s and the early 690s, Armenian architecture saw its first ‘Golden Age’. During that brilliant time, dozens of high-quality, original, and innovative religious structures were built in Armenia. These domed buildings, with their complex and thoroughly planned compositions, had fine and unique sculptural ornamentation. After the construction of Zvartnots, beginning from the mid-seventh century, architectural sculpture acquired a uniqueness unusual for Armenia and even some luxury. Within the same period, the type of monuments with column or cross-crowned quadrilateral carved memorials was also developed. Moreover, that rapid upsurge of Armenian architecture and sculpture occurred in the period when the other major Christian centres of the East, such as Byzantium and Syria, were experiencing deep crisis, and almost no significant structures were created there.

- In the sixth and seventh centuries, the Armenian Church had a clear favorable position in regard to wall painting and struggled against iconoclasm. In Armenia, one of the standard bearers in defence of iconography was the chronicler Vrtanes Kertogh. In his work About Iconoclasts, to contradict the opponents of iconography, he brings forward the following argument: ‘it is not because of the colours that one prostrates, but because of Christ, for whom they are painted. . . . We recognize the invisible through the appearance of God, and the colours and images are the memories of the Lord and his servants’. As an additional argument, Vrtanes Kertogh presents a rather long list of subjects painted on the walls of Armenian churches, opposing them to the idols erected in pagan temples.

Under such circumstances, it is natural that monument painting received a

powerful impetus. And actually, there are many traces of the paintings preserved on the internal walls of some seventh-century Armenian churches. However, until recently, the number of fragments of visible images was too small. Only four monuments with remnants of ‘readable’ wall paintings were mentioned by the scientific community. Those are the churches of Mren, Lmbat, Arutch, and Talin, with the fragments of paintings preserved in the altar apse and on its conch as well as some minor leftovers of images preserved on other walls. Unfortunately, the Mren church, which lost its southern wall nearly twenty years ago, today stands on the verge of collapse, and, being situated on the Turkish side of the Armenian border, is almost inaccessible.