By Sadie Cruz

PLATTSBURGH, N.Y. (Press-Republican) — Millions of dormant accounts owned by Jewish people during the Holocaust still rested in Swiss banks in the late 1990s.

That’s when a scandal broke, revealing that the monies were never returned, which led to a lawsuit that eventually issued $1.24 billion to Holocaust survivors and their heirs.

The mystery of the hidden millions would change the way the world looked at Switzerland’s history in relation to World War II.

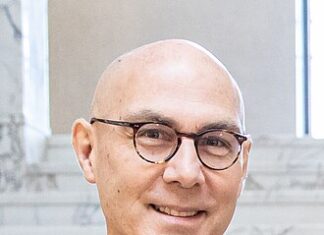

Emmanuel Tchividjian, who describes himself as Judeo-Christian, grew up in Switzerland and later moved to Boston. He embarked on a personal mission to right the wrong that he felt was 50 years overdue.

He was at State University of New York (SUNY) Plattsburgh recently, as part of the Douglas R. Skopp Speakers Series on the Holocaust, to talk about his role in the historic case and how the public-relations firm Ruder Finn, where he used to work, played an influential part in making the Swiss banks agree to restitution.