Mirror-Spectator Staff

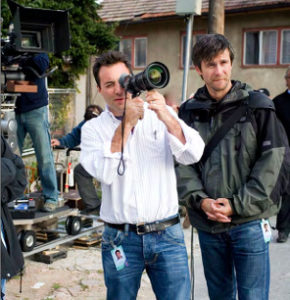

LOS ANGELES — Richard Shepard is an independent film and television director and screenwriter who has been recently vaulting from one success to another. The television pilots that he has directed for the shows “Ugly Betty,” “Criminal Minds,” “Criminal Minds: Suspect Behavior” and “Ringer” have successfully led to serialized television shows, and Shepard won an Emmy Award for Outstanding Directing and a Director’s Guild of America award for “Ugly Betty” in 2007. Shepard’s 2005 film, “The Matador,” starring Pierce Brosnan, Greg Kinnear and Hope Davis, received enthusiastic reviews. His most recent film, a dark comedy called “The Hunting Party,” with Richard Gere, Terrence Howard and Jesse Eisenberg, was shot on location and deals with modern political issues. His documentary, “I Knew It Was You: Rediscovering John Cazale” (2010) is a favorite of movie buffs.

Shepard, a native of New York City, continually encounters Armenians in all walks of life in Los Angeles. He said, “As soon as I hear a name which sounds Armenian, I say my mom is Armenian and we start talking about it.” His father’s family was originally from the Austria-Hungarian Empire, and exposed him to aspects of Jewish culture. Shepard noted that there are filmmakers who have tapped into their childhoods and backgrounds in a specific way to make their films. Atom Egoyan is a good example. Shepard, however, is not one of them. His childhood and cultural formation manifest themselves in his work through his worldview.

He explained, “I consider myself very lucky in the weird rich complex of back- grounds that I grew up with. It contributed to my development as an artist and a human being, my way of looking at things, and my attitudes.” Shepard was exposed to different cultures and languages, leading him to become artistically open, and flexible in life. He said, “I remember as a child going over to Grandma’s house, and people were speaking languages that were not English. I can eat any food, and travel almost anywhere. I have shot movies all over the world in places most people have not gone to.” Despite this general influence, Shepard has not so far made works delving directly into his past, observing, “More specifically, that hasn’t been the case, but who knows where it may lead?”

Both of Shepard’s parents were artists in different ways. Shepard’s passion for movies was shared with his father, who would take him to revival theaters as a child. Shepard said, “I think that as soon as I realized that I was not going to play third base for the New York Mets I shifted my priority to making Super 8 movies, when I was about 12 or 13 years old. I educated myself, getting magazines and books to learn how to do little tricks and visual effects. I was influenced by real movies I was seeing. It is such an incredible way to express yourself. Then eventually I realized it was what I wanted to do, and truly the only thing that I was at that point capable of doing.”