By Jessica Dello Russo

Special to the Mirror-Spectator

BOSTON — The Armenian Heritage Park on The Greenway is one of the main entrances to the North End/Waterfront neighborhood from the Wharf District and Faneuil Hall. Its size and location make it hard to miss as you walk through the Rose Kennedy Greenway. A closer look rewards you with more insight into the Park’s features, such as a walkable Labyrinth, towering, shape-shifting Abstract Sculpture, fountain, and benches around the Park’s leafy enclosure. The Park’s accessible layout offers visitors various ways to engage with the space. As a close neighbor, I walk by the Park almost daily while entering and exiting the North End.

Decades ago, I would have only overheard the cooing of pigeons perched on the rusting steel beams of the old Fitzgerald Expressway. I have vivid childhood memories of noise, darkness, stagnant water, decaying litter and a host of unpleasant smells in the area where the park now stands. At the time, I was too young to comprehend the consequences of the highway’s impending demolition and the changes to follow.

An invitation to speak about Italian heritage in the North End as part of the Park’s series, “Celebrating What Unites Us!” co-sponsored by the Friends of Armenian Heritage Park and the City of Boston’s Office for Immigration Advancement, not only inspired the personal reflections shared above, but also genuine curiosity about the connections between the Armenian and Italian communities in Boston. Despite the city’s historical parochialism, interactions among native Bostonians often lead to personal connections (as it turns out, the event organizer, Barbara Tellalian, and I had attended the same grade school).

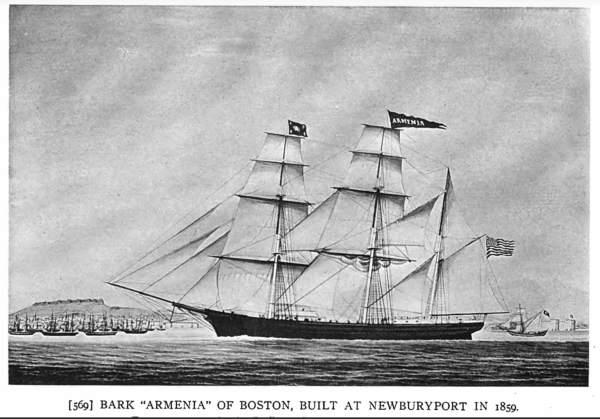

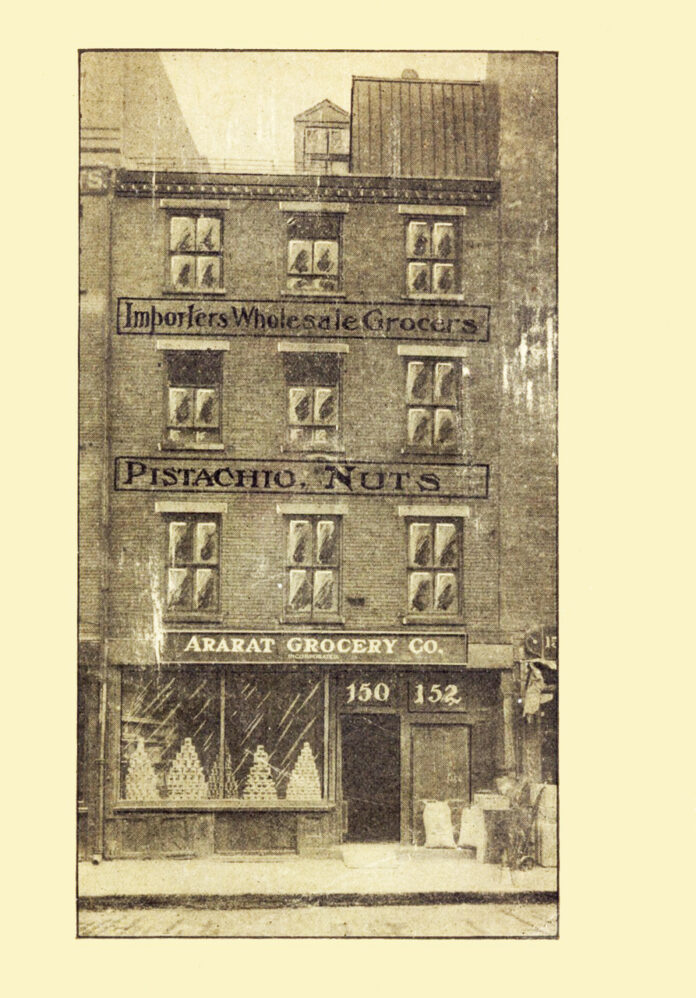

Thanks to my involvement in a recent photo digitization project focused on the North End, I was already aware of a fascinating Armenian-Italian connection in Boston that dates back to the China Trade Era, from 1783 to the 1850s. The photo I had in mind depicts a group of Italian Americans with the men in uniform and their elegantly dressed wives, all standing in front of a statue of Christopher Columbus. The iconic backdrop of this scene is undoubtedly Louisburg Square.