By Larry Luxner

Special to the Mirror-Spectator

For decades, Armenia and Israel have had every reason to be close — yet were blocked by geopolitics. That may now be changing, thanks to an under-the-radar drama on the world stage.

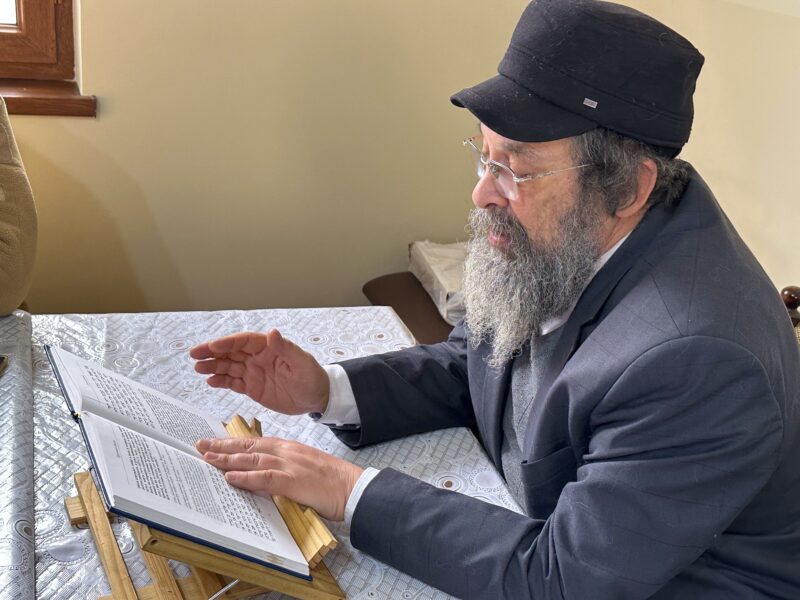

It would be a long-overdue correction for the many Israelis and Armenians who see each other as natural partners: two small, non-Muslim democracies in a region dominated by authoritarian regimes; ancient peoples with deep diasporas and deep memories; communities that lived as successful minorities under Soviet rule.

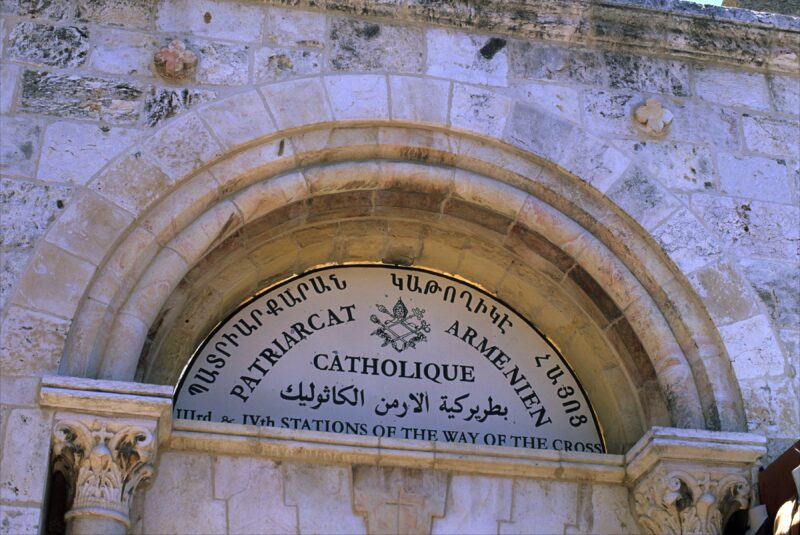

Armenians have maintained a presence in Jerusalem since the 4th century, and Jews have lived in Armenia for centuries. And both nations endured genocide in the 20th century — the Ottoman slaughter of Armenians in 1915 and the Nazi extermination of European Jewry.

Yet those shared experiences never translated into trust. Israel’s strategic alignment with Azerbaijan — Armenia’s rival — long overshadowed everything else. Azerbaijan supplies Israel with oil and access to Iran’s northern flank, and in return has been a major buyer of Israeli drones and precision weapons. Those systems proved decisive in Baku’s victory in the 2020 war for Nagorno-Karabakh, and in the 2023 campaign that emptied the enclave of its 120,000 ethnic Armenian residents.