NICOSIA — More than 30 years after the establishment of bilateral relations, Armenia has at last opened an embasssy on the Mediterranean island of Cyprus.

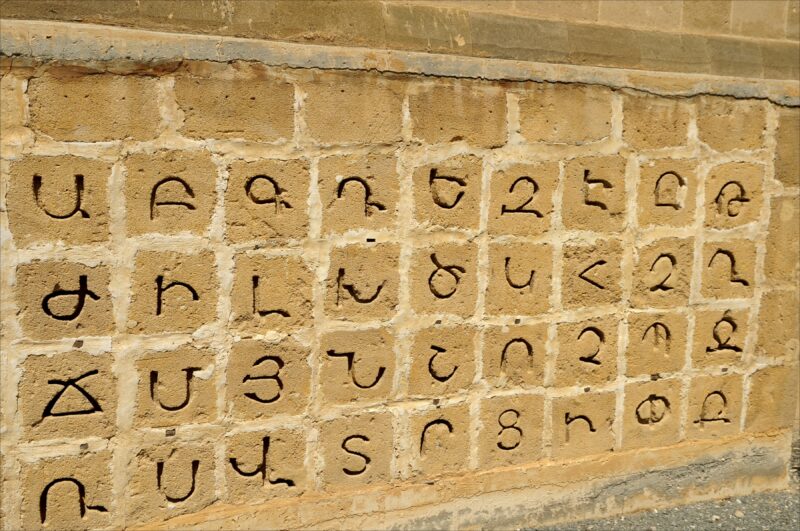

It’s an important milestone for both countries, which share a common Christian faith as well as a bitter legacy of repression by Turkey and its predecessor, the Ottoman Empire.

“Armenia and Cyprus have had deep, historic ties for centuries,” said newly appointed Ambassador Inna Torgomyan, who on May 2, 2025, presented her credentials to Cypriot President Nikos Christodoulides in Nicosia. “There’s a longstanding friendship between our peoples, and these bonds have created a strong sense of solidarity. Even before establishing embassies, we have worked closely in many areas, including defense,” she said.

Until now, Cyprus had fallen under the jurisdiction of Tigran Mkrtchyan, Armenia’s resident ambassador to Greece; from Athens, he also had responsibility for neighboring Albania.

In September 2024, Michael Mavros became the first Cypriot resident ambassador in Yerevan. Martiros Minasyan will remain Armenia’s honorary consul in Limassol, the island’s chief port. The embassy is expected to begin offering consular services in September or October.

Torgomyan, 42, spoke to this reporter by phone from Armenia’s new mission on Akadimou Street in the Engomi district of Nicosia. That’s a five-minute drive to the buffer zone that separates the Greek-speaking Republic of Cyprus — a member of the European Union — from the self-proclaimed “Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus.”