By Larry Luxner

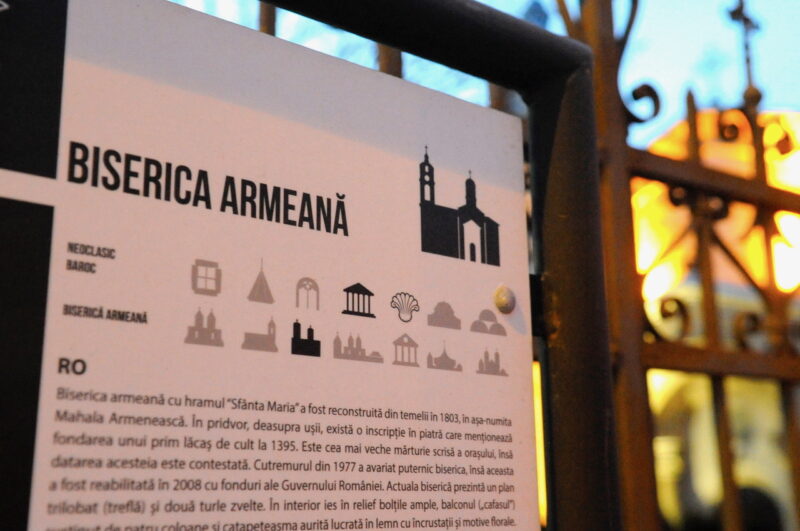

DUMBRĂVENI, Romania — Dominating the main square of this sleepy Transylvanian town 20 kilometers west of Sighișoara — home of the fictional Count Dracula — an Armenian church stands witness to the ravages of time.

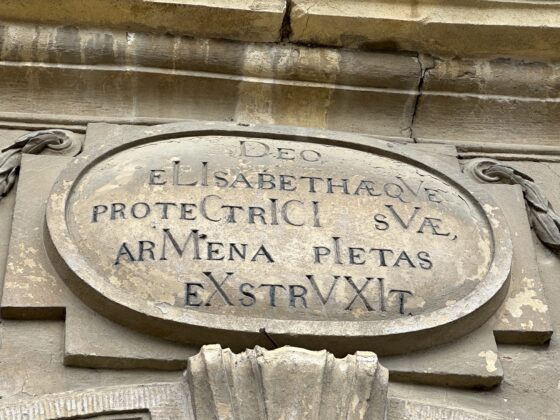

Known as the Biserica Armeano-Catolica St. Elisabeta, the Baroque granite-and-brick structure bears this Latin inscription: “He who loved God built this cathedral between 1766 and 1791, with seven altars and three types of stained glass, for us, who live in the present, and for future generations.”

Like the church itself, which seems badly in need of restoration, the community it was built to serve does not have much of a future.

About 500 ethnic Armenians once lived here, but today, Dumbrăveni is home to maybe half a dozen. Across the plaza is a pink monastery that now houses a grocery store and bakery. Nobody in town can read the delicate Armenian script carved above the former monastery’s entrance.

“That community mostly disappeared after 1920, because Transylvania became part of Romania and they spoke Hungarian. So most decided to emigrate to Hungary,” said Attila Kálmán, vice-president of the Armenian-Hungarian Cultural Association of Târgu Mureș. “Only the old buildings and the cemetery are left — and all the tombstones are in Hungarian.”