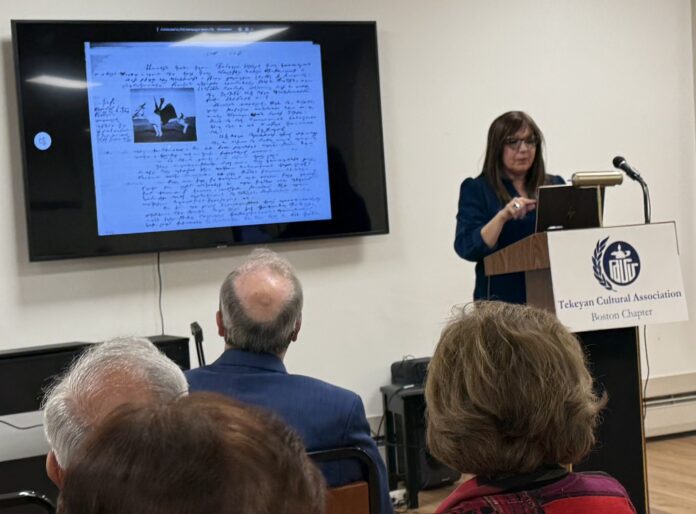

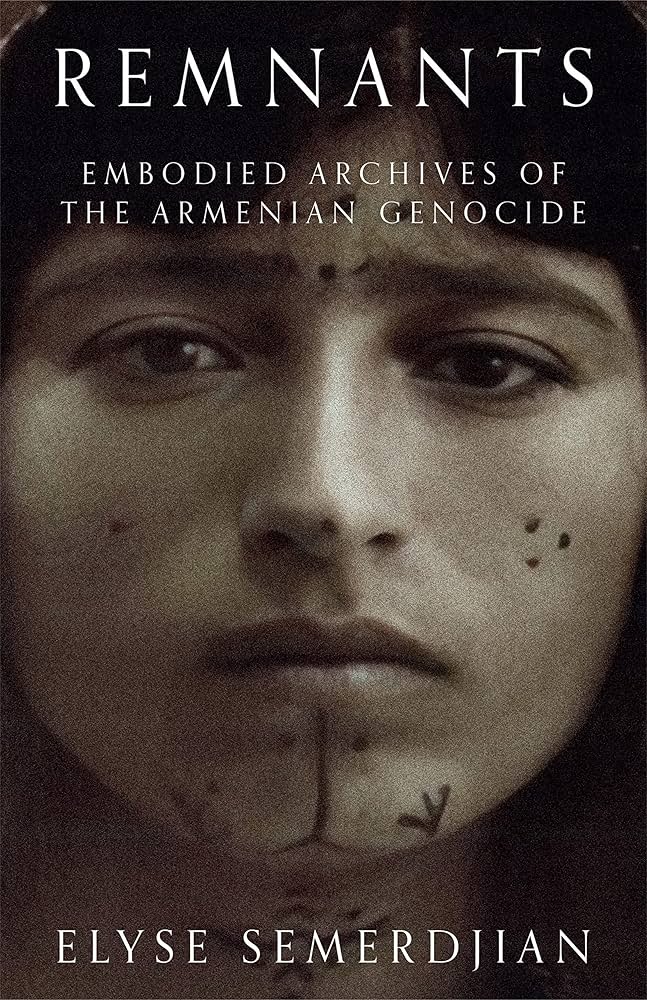

WATERTOWN — Dr. Elyse Semerdjian gave a talk about her recent book, Remnants: Embodied Archives of the Armenian Genocide (Stanford University Press, 2023), for the Tekeyan Cultural Association (TCA) Boston Chapter at the Baikar Building, on April 11.

Semerdjian holds the Robert Aram and Marianne Kaloosdian and Stephen and Marian Mugar Chair of Armenian Genocide Studies at the Strassler Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies at Clark University. Previously a professor of Islamic World/Middle Eastern History and Chair of the History Department at Whitman College (Walla Walla, WA), she is a specialist in the history of the Ottoman Empire, especially Ottoman Aleppo and the Armenian community, and author of “Off the Straight Path”: Illicit Sex, Law, and Community in Ottoman Aleppo (Syracuse University Press, 2008).

After her introduction by TCA of the US and Canada Executive Director Aram Arkun, Semerdjian noted that as a scholar of gender, part of her aim was to write women into the historical record, and her recent book speaks to how gender and the body figured in the minds of perpetrators and humanitarians.

She provided background information on the Genocide and the rescue and recuperation efforts that followed with a focus on gender, including the initial feminizing of the Armenian population by removing and killing males, and the Ottoman historical background of female abduction, forced marriage, slavery and domestic labor.

Semerdjian gave credit to scholarship in Bosnian and Rwandan studies, which opened the way for analyzing attacks on lifeforce, reproduction and mass graves in genocide. While continuing to use available archival materials such as in the Ottoman state archives, she attempted to expand her sources using interdisciplinary skills to read memoirs, letters, newspapers, biographies, oral histories, ethnography, photography and even some film. She highlighted stories of violence central to the Armenian Genocide but often relegated to short sections in the standard texts. She called these cyphered bits of information “remnants,” and considered the physical bodies of survivors a repository of traumatic experience, as well as sites of resistance.

She used the terms postmemory or prosthetic memory for how sometimes people feel as if they have experienced something though they have not. This is understood through affect theory, and she mentioned in particular the work done by Marianne Hirsch on the Holocaust in this regard. She gave the example of Suzanne Khardalian’s 2011 documentary film “Grandma’s Tattoos.” At a point in the film, it becomes clear that the grandmother’s experiences of shame had been absorbed by Suzanne herself as postmemory, almost as if they were her own memories.