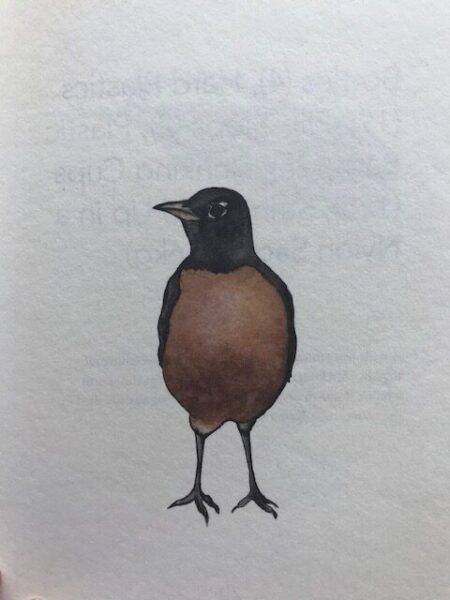

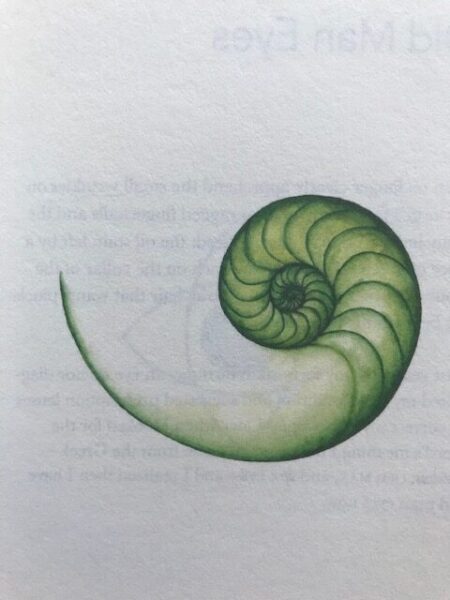

small pieces (Dalkey Archive Press, 2023) is truth distilled to its purest essence. Through conversations, spoken and unspoken, over distance and in time, two women, a writer and an artist, both in their late 40s, reach deep into their souls to access the truth that resides in the “dim interiors of the self.” “I am and I am and I am in the pages of books,” avers visual artist Fowzia Karimi, creator of the watercolors paired with pieces written by Micheline Aharonian Marcom, the celebrated author of seven novels. small pieces compresses the artists’ exchange into twenty-five beautifully rendered texts and images.

The texts, each about a page or less long — Micheline calls them “miniatures” — are stunningly condensed. There is not a word to skip or a line to jump. In just a few sentences, “Time Apart” conveys a young woman’s anxiousness, as she watches the hands of the clock that will bring her lover “to his home . . . for dinner at six-thirty,” so they can be “together again.” In another piece, in just four lines, Marcom shocks the reader into consciousness of mankind’s abuse of the holy environment. “A wide assortment of synthetic polymers weighing all together 5.9 kilograms were extracted from the sperm whale’s stomach after the young male had already died in the waters near Kapota Island,” she writes.

“The book has been a long time coming,” says Fowzia in “Dialogos,” a candid conversation that reveals the relationship each woman has to her art. Fowzia’s “I write and paint to get to the truth, the essence of a thing,” echoes Marcom’s “The writing life is a slow, yet continual awakening to higher levels of awareness, of consciousness, from the various mirages that pass for ‘reality.’” small pieces celebrates this higher level of consciousness.

It is, in fact, humanity’s move away from this transcendent reality, the spirituality rooted in each one of us, and excessive focus on the “things . . . for sale inside the monstrous retail store,” that Marcom laments. The anguish the two women feel over the destruction of the natural world is at the core of their thinking.

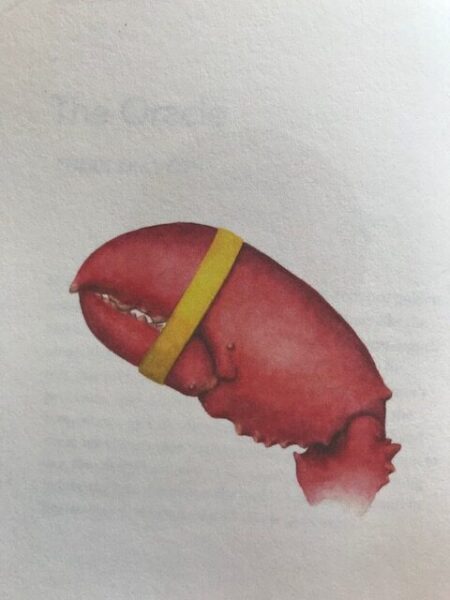

In “Both Beautiful and Strange,” Aharonian joins in her young son’s excitement to see the solar eclipse. She celebrates “The Miracle of Photosynthesis and Its Waste Product,” while she deplores mankind’s abuse of the creatures inhabiting the sacred Earth. Marcom mourns the otters that have been slaughtered to extinction, bees just disappearing to insecticides, and the lobsters in supermarkets, whose front paws have been clamped with “thick red and yellow rubber-bands” to restrict their mobility — all done for profit and greed.

Aharonian also bemoans the brutal killings and the needless loss of human lives. “The dry riverbed, the not road . . . to Der Zor . . . the abandoned villages and bones of the old Armenian clans in old Turkey; the newer (unrecovered) ghostly dead in Afghanistan,” evoke the bloody histories of both women. Wars have disrupted their lives. They now live in a new world: “We can none of us ever return.”