By Aida Zilelian

It seems impossible to memorialize the life of a prolific translator a decade after his passing. Especially if you knew him for much of your life. I looked at my calendar today and it marks eleven years this May since Aris Sevag died. I don’t reflect on how much time has gone by. For me, his death stands still. It was only after his passing that I was able to understand who he truly was, beyond his life’s work and his care and love for me as my stepfather.

For the Armenian community, Aris was a treasure. He edited and translated hundreds of literary works from Armenian to English interchangeably, bringing to life excerpts, articles, books, and memoirs of Armenians who would have long been forgotten had it not been for his voracious — compulsive, really — desire to extract the meaning of words in its purest divination. I recently discovered that a collection of short stories, seven of which he had translated, Armenian-American Sketches by Bedros Keljik was selected as the winner of the 2020 Dr. Sona Aronian Book Prizes for Excellence in Armenian Studies. Aris’ bibliography could fill volumes. One of his most notable masterpieces was his translation of Armenian Golgotha (2010, Knopf), a 500-page memoir by the priest Grigoris Balakian, who was arrested and deported during the Armenian Genocide, where he bore witness to the annihilation of his people.

Aris told me once, “To say this is devastating to read…. It can take years off your life.”

He recounted the stories of his father, a professor of Physics, Dr. Manasseh Sevag, who was a Genocide survivor and a professor at the University of Pennsylvania.

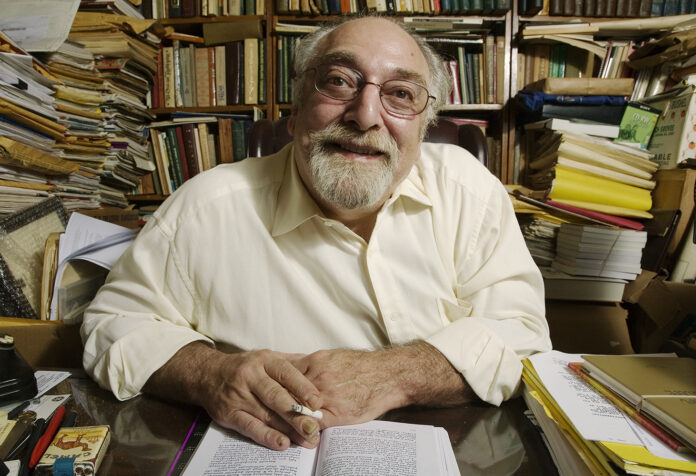

The only way to truly understand his dedication to his craft, his passion for words and knowledge, was to step into his study, as I did for many, many years. He had so many books, custom shelves were built to fit his study from floor to ceiling. His desk was surrounded by a fortress of dictionaries and thesauruses. Oftentimes, one had to call out to him or look over the towering stacks to see if he was in the room. Somehow he was able to fit a clock radio (which perpetually played classical music), an amber ashtray, a small, high-powered fan and his asthmatic printer, alongside his collection of books. It was comedic, really. He lived and breathed, ostensibly, to edit and translate. In his leisure time, I would catch him in the middle of proofreading anything he saw in print — a restaurant menu, a poster on the subway, a billboard sign, a playbook at the theater.