In a sometimes forgotten corner of Asia Minor, amid the ruins of a former Soviet republic turned capitalist hell hole, in a land where a brutish individualism has taken hold and where a handful of oligarchs live in unimagined luxury while the rest of the country starves, atop a hideously smoldering trash dump where the denizens of the once model community of Nubarashen are reduced daily to foraging with rats and dogs for food, Denis Donikian sets his remarkable novel Trashland.

Trashland begins with its hero Gam standing atop a hill, relieving himself on the Armenian capital of Yerevan below. (Gam, which in Armenian means both “I exist” and “or” — a clever play on words.) Gam then joins some trash pickers and mourners as they follow the burial procession of a woman named Anna, who turns out to be his mother. Once a muckraking journalist nicknamed The Hedgehog, Gam fled a life-shattering earthquake in his home city of Gyumri and the henchmen of the Armenian government into a small hut near the garbage dump. Here he has escaped society. Hook and shoulder bag in tow, he joins Roubo and Lousso and their motley group of friends to daily pick for food among the trash. One day the government henchmen arrive: the Japanese have been hired to install an efficient incinerator system and everything — and everyone — must go. The rest of this tale involves many twists, turns and ironies. Interestingly enough, the great Armenian writer Vahan Totovents wrote about trash pickers (or kulkhan beyi in Turkish) in his 1930 novel Life On the Old Roman Road. It’s a sad but telling comment on how precious little social equity had been gained in that part of the world over the past 100 years.

Few novels deliver quite so biting, acerbic and at times joyful societal criticism as Trashland. The novel serves as both a dirge (and underneath it all, a paean) to a country abandoned to its worst tendencies where, in real life as in fiction, women who are forced to prostitute themselves with their historic enemies in Turkey or journalists who dig a bit too deeply at the country’s corruption, or anyone who simply openly disagrees with the government are “disappeared” or “suicided” off the frightening Kiev bridge with alarming regularity. Trashland owes a debt to both William Golding and George Orwell. Instead of an island as in Lord of the Flies, Donikian presents to the reader an Armenian trash dump. Instead of an allegorical animal farm as in the eponymous novel, the author gives us a whole country turned into a zoo, its people no better than farm animals to be exploited, metaphorically consumed, and then discarded.

Trashland was received with dismay by many of Armenia’s so-called intelligentsia. Everything from the title to the brutal honesty of its narrative took many by surprise. Just as Junot Diaz’s The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao takes a candid look at the Dominican community in New York City and the DR, Trashland offers an insider’s view at a sometimes closed-in society. As a diasporan Armenian, Donikian writes from the viewpoint of both insider and outsider. In going farther than most diasporans and openly criticizing a rotting society, he has crossed the line assigned to most diasporans — mere cash cows to be bilked at will for imaginary projects, or retirees who come to spend their hard-earned money in their golden years. To cross this line, one must love one’s people and community. To lay bare its deepest wounds and expose its most deep-seated corruption — those are the signs of a true patriot and humanist.

Writer and philosopher Marc Nichanian has noted that Armenian writers of the diaspora have labored within a self-contained world with an imaginary and yet very real curtain separating them from Soviet and now independent Armenia on the one hand, and the rest of the world on the other. Let’s hope that Trashland, published first in French by a leading publisher — Actes Sud — and now picked up in its English translation by the fine independent publishing house Nauset Press, will help to pull this curtain back and perhaps, Oz-like, reveal this fascinating and complicated culture to the world-at-large and the reality that lays underneath.

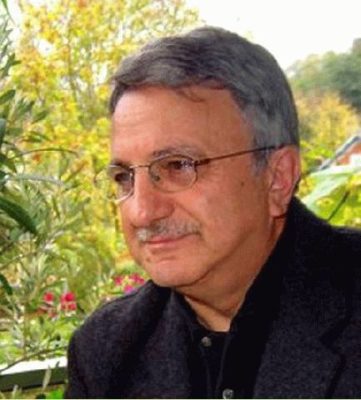

Trashland is a liminal novel, written from the perspective of an insider/outsider. Denis Donikian was born 1942 in Vienne, a small city just south of Lyon, France, and grew up in Le Kemp, a former armaments factory housing workers who were all Armenian Genocide survivors. He studied first in France and then in Soviet Armenia while still a young man. He has spent the better part of his adult life writing about and critiquing life in the Armenian diaspora and the Republic of Armenia both. Donikian has published some forty books, including tomes of poetry, a long extended poetic essay on Paradjanov’s horses that to this day remains singular in its beauty and passion, as well as exhibited his wonderfully quixotic sculptures influenced by First Nation totem poles. His recent Small Encyclopedia of the Armenian Genocide, a monumental six-hundred page thematically arranged history of the Great Catastrophe or Medz Yeghern, is in part a devoir de mémoire and a nod to his parents who survived the event and managed to transmit Armenian culture and language to their son. The greater part of Donikian’s oeuvre then, including his journalistic work at www.yevrobatsi.org where he was my very brilliant editor, has been a long, extended critique of the Armenian world and a quest for justice for the Armenian people. His work is living proof that the two are not mutually exclusive.