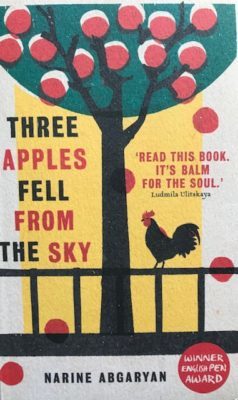

In Three Apples Fell from The Sky (Oneworld, 2020), author Narine Abgaryan takes us to the heart of Maran, a village perched on a cliff in the Armenian highlands, at the farthest end of Manish-Kar.

Abgaryan brings this isolated mountain village to life with her vivid, often hilariously funny, details and playful images. With painstaking detail, she describes the “tangy scent of tiny, delicately blushing apples with dark raspberry-colored seeds and little pink blotches on the cut edge,” or a pig “that particularly astounded the Maranians because it was as clean and neat as a round turnip that had been thoroughly washed under running water.”

We walk through the village roads and climb the perilous mountain path, rejoicing in the winter snow, the pale blue alpine violets, and the pink and white almond and cherry blossoms. Abgaryan allows us to participate in the ways of the villagers, as they gather over strong tea with thyme, tend their kitchen gardens, and help one another cook, babysit and care for the ill.

The book opens with the 58-year-old Anatolia, the youngest inhabitant in Maran, waiting to die. “If only I could hurry up and die,” she moans as she lies in bed soaking in blood from a sudden onslaught of her menstrual cycle. The final image of the novel is not of the finality of death, however. Anatolia gives birth to Voske (miracles are taken for granted in Maran), a baby girl born of her second marriage to the caring Vasily, with “the village of old people” happily sharing in the responsibility of raising a new child. Voske may know nothing of “the big wide world,” but she had her own tiny world over which “stretched an endless summer’s night that told stories about the power of the human spirit, about devotion and nobility,” writes Abgaryan.

“The Maranians were a rational people who nevertheless believed in dreams and signs,” we are told. They believe, for example, that dreams dreamt “on Wednesday mornings, between the rooster’s first and second crows” have a hidden meaning. Indeed, because of a prophetic meaning attached to the dreams of Akop, an inhabitant known for his ability to foresee misfortunes, the villagers construct a stone barrier between the peak and the houses to the east, which actually prevents the mudslide from reaching the village and tumbling it into the valley below. In this fantastical tale of superstitions and unusual occurrences, the magical and the real mix seamlessly. The cesspit overflows, spills over, and floods part of Anatolia’s yard when the packages of expired yeast, which hadn’t lost its strength, are thrown into the cesspool.

The remote rural setting of the novel suggests the simplicity and the innocence of a world of “endless summer nights” and “many wonderful things.” This world is, nonetheless, also a world where life’s hardships never ease. Famine, war, and earthquakes are constant occurrences. Death is a fact of life in Maran. When war breaks out and Maran’s men are drafted, the village is “reduced by half,” and plunged into “pitch-black darkness, hunger and cold.” Over the years, all the children are lost to famine. Indeed, the solitary village, with only twenty-three inhabited homes, may be “meekly living out its last years as if condemned, Anatolia along with it:” “The young people had gone and the old ones would depart without even leaving behind memories.”