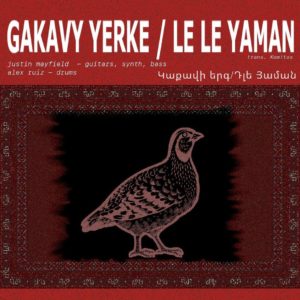

WATERTOWN — The classics of Armenian folk music may seem eternal, passed down from one generation to another. Yet variations and new interpretations always arise, whether regionally or over time. Today it is no different. If that music is going to remain something vital, it will be open to reinterpretation by new artists, and guitarist and audio engineer Justin Mayfield of Brooklyn, New York is doing his best to keep that music alive, starting with his inaugural digital album, “Ghedtair Composite.”

Justin described the journey which led him to this project, declaring: “I think my story is pretty common with a lot of diasporan Armenians who were not exposed to the culture growing up but find the interest later in life and start to try to educate themselves. It has all been my own self-education after graduating college and going to Armenia for the first time in 2014. It has been like filling in holes.” He waggishly observed in his online notes to his album on bandcamp.com that “my childhood was more bacon than sujuk; more soccer practice than Armenian language lessons.”

Becoming a Musician

The 33-year-old grew up outside of Boston in Upton, a town fairly close to Worcester, in a musical environment. Justin said he always wanted to play an instrument. He learned violin as a young child through the Suzuki method with his mother, and in middle school learned to play saxophone, but his father always had guitars around the house. As Justin explains it, “My dad was a guitar player and an audio engineer himself, so it came from him putting a guitar in my hands at a young age.”

His father, who used to record in studios on tape and do all the manual, physical tape work for editing, also somehow passed that interest on to Justin, who recalled, “I remember recording on a tape machine, teaching my sister how to play and sing some simple parts, so I could record two people at the same time.”

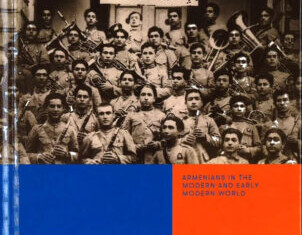

His mother is Armenian, and Justin was fortunate to have gotten to know his maternal grandparents, and even his great-grandmother. He said, “I grew up with my grandmother and great-grandmother. I had this feeling of guilt for not knowing where she [great-grandmother] came from. I knew her basic story of coming to America during the Genocide. My dad in 1982, before my sisters and I were born, sat my great-grandmother down and recorded her telling her story on a tape machine [together with Justin’s great-grandfather]…She was born in Marash and my great-grandfather was too. They came through France [to the US]. It is funny — my fiancée’s family came from there as well.”