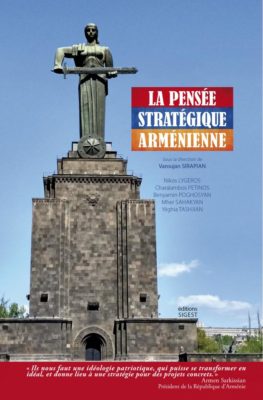

The shock of the grave Armenian defeat in the 2020 Artsakh war has naturally led to various efforts to figure out what went wrong and perhaps more importantly, what Armenians need to do to avoid further catastrophes. The collection of articles published as the French-language volume La Pensée stratégique Arménienne, edited by Varoujan Sirapian and published by Éditions Sigest in Paris in 2021 with the assistance of the Tchobanian Institute, is a step in this direction. It is an attempt to promote strategic thinking concerning the military, economy, law, sociology, communications and propaganda, demography and international relations. The 164-page book includes chapters by Sirapian, Nikos Lygeros, Charalambos Petinos, Benyamin Poghosyan, Mher Sahakyan and Yéghia Tashjian.

Each chapter can be read as a self-contained article, with few direct references to the other sections of the book even though there is some overlapping coverage. The authors all seem to be partisans of the creation of a stronger Armenian state in the future to better defend the interests of Armenia and Artsakh and accept the importance of Russia’s role in the region, though some find it less reliable than others.

Sirapian on Defense

The longest contribution is by Sirapian at the start of the book. Sirapian is a frequent writer in the Armenian press in France, North America, Lebanon and Armenia, the author of a number of books, and founding president of the Institut Tchobanian (Alfortville, France). He proposes instead of lamentation an analysis of the causes of the defeat be conducted in order to find means to rectify the situation. The most important Armenian objective should be to move from being an Armenian people to an Armenian nation embracing both diaspora and homeland, according to Sirapian.

Among the most important realms requiring strategizing, he says, are the reformation of the army to assure the security of the country, the establishment of a state of law with a reliable independent justice system, improvement of the demographic situation, and inculcation of the notion of obligations and rights for Armenian citizens.

Sirapian stakes out the problems in the approach to such issues in Armenia. He points out that the lack of an independent Armenian state over a period of nearly 600 years, aside from a little over two years at the start of the 20th century, seriously handicapped the creation of strategic political thinking and a political elite to carry it out. The current independent Armenian republic has dozens of political parties but has not succeeded “during these three decades to put into place a sane and democratic political life where ideas (and not persons) can oppose one another without violence in order to arrive at a well-defined objective, even with different methods” (p. 20).