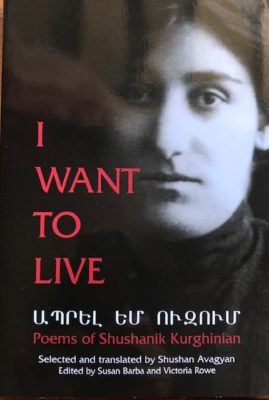

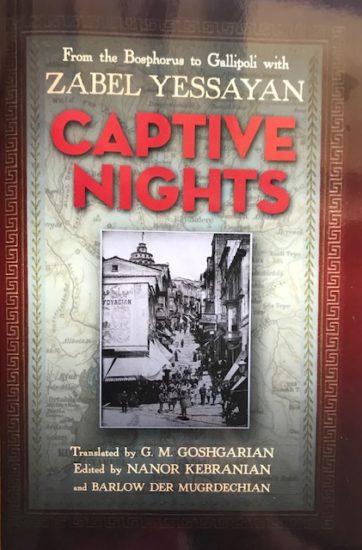

LOS ANGELES — On a recent visit to ABRIL bookstore in Glendale, I picked up copies of Zabel Yessayan’s Captive Nights and of Shushanik Kurghinian’s I Want To Live. While I was familiar with Yessayan, and had read some of her oeuvre, I was on an adventure to discover Kurghinian. As I read on, I was struck by the daring of the two women, both writing in the early decades of the 20th century, in demanding the fair treatment of all oppressed groups.

“Every trace of servitude must be/uprooted, demolished, undone!” vows the speaker in Kurghinian’s “A Curse.” Likewise, seated next to her little one’s cradle, the narrator in Yessayan’s Enough!, one of the three novellas in Captive Nights, summons her little one “to struggle, so that your head is never bowed in servility.”

Kurghinian’s is a passionate plea for a woman’s right to live fully. The boldness of:

Do not love me gently as if

I were a blooming flower in spring,

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . .