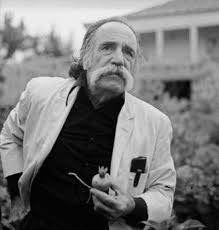

I have a confession to make. Growing up and throughout my youth, I was not a fan of William Saroyan. Like much of the New York Establishment, I found his writing quaint — provincial in the bad sense. I would re-read his short stories and wonder if Armenians just liked him out of misplaced chauvinism.

Saroyan also seemingly disappeared from high school and college curricula after his death in 1981, so I no longer gave his work much thought. In article after article, purported personality flaws had helped to sink his reputation: the bard of Fresno had a flamboyant personality which enchanted some but irked others — but much like Lillian Hellman stateside or Françoise Sagan in France, I always found comments about his personal life misguided at best. When women or minorities gambled or drank, it became newsworthy — when Hemingway or Fitzgerald did the same, it was somehow macho, almost commendable. As another son of Fresno Mark Arax put it, by the early aughts Saroyan qualified as “the most famous forgotten writer of the twentieth century.” So it was with both trepidation and keen interest that I first decided to listen to a seven-part series of recordings on Central Valley Public Radio produced by Arax, each story accompanied by a discussion of its relevance. There was also, I read elsewhere, a new Saroyan House Museum in Fresno: watch out world, Saroyan seemed to be making a comeback.

That I could have so misjudged a writer fairly boggles my mind. Each exquisite text in the series, each one read by a different Fresno writer, delights both ear and mind. It turns out that Fresno, or the “Big Raisin” as it was euphemistically called in the 1970’s and 80’s, is home to a colony of talented writers and poets.

I name them here to salute their own individual talents — I made it a point to familiarize myself with their work as well and each one is worth a read: Kenneth Chacón, Brynn Saito, Aris Janigian, Marisol Baca, Tanya Nichols and of course Arax himself.

In Saroyan text after Saroyan text, I (re)discovered a writer garrulous and funny, ingenious and surprising — someone in whom sentimentality is but a front for an almost Zen-like simplicity of style and thought. If you will pardon the overused oenological metaphor, like fine wine Saroyan gets better with time.

A minimum of research also reveals that for the pre-World War I and II period that he grew up in, Saroyan’s writing was in fact bold and original.