By Artsvi Bakhchinyan

Special to the Mirror-Spectator

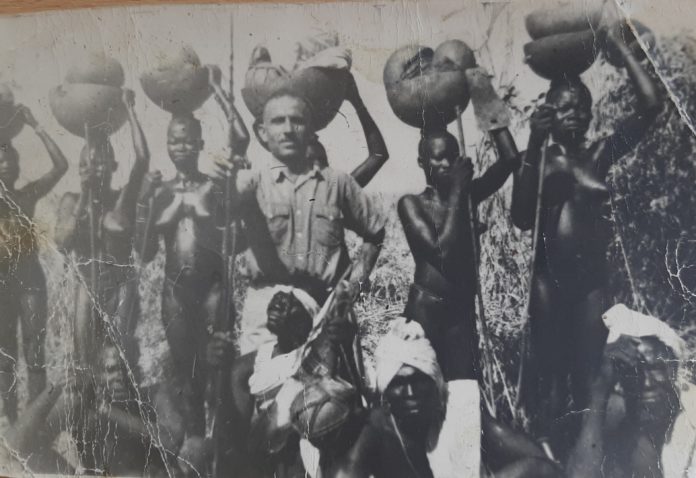

YEREVAN — In the distant 1980s, during one of the faculty English lessons at school, classmate Azatuhi Ulikyan showed us a family photo. “This is my grandfather in Sudan,” she said.

In the middle of the black-and-white photo was a man surrounded by half-naked women and men. What a surprise! So the grandfather of one of our schoolgirls in this gray Soviet school lived in distant and exotic Africa and was photographed with the people of one of the local tribes, whose women were half-naked! That photo left a strong impression on me. A few years later, based on that, I drew a small painting. And many years later, studying the history of African-Armenian communities, I remembered that photo and decided to follow in the footsteps of Sudanese-Armenian Ulikyan.

I found Azatuhi Ulikyan, now the holder of a doctorate, and an associate professor at the Control Systems Chair of the National Polytechnic University of Armenia and Educational Engineer at the Armenian National Engineering laboratories. She introduced me to her uncle, Andranik Ulikyan, who was born in Sudan. The latter gladly agreed to tell the extremely remarkable story of his family, which I present below.

African Deportation