By Arthur Hagopian

JERUSALEM — The advent of Christianity and its adoption as a state religion by Armenia provided an unparalleled opportunity for the resurgence of artistic fervor among the newly converted, resulting in the creation of some of the country’s most elaborate works of art, particularly in the domain of miniature illustration.

The artists set about their joyous task with abandon, evident in the masterpieces that they have bequeathed to us down the ages, their brushes delving not only into the pages of the gospels, but probing into the non-biblical domain, including the apocryphal, as well.

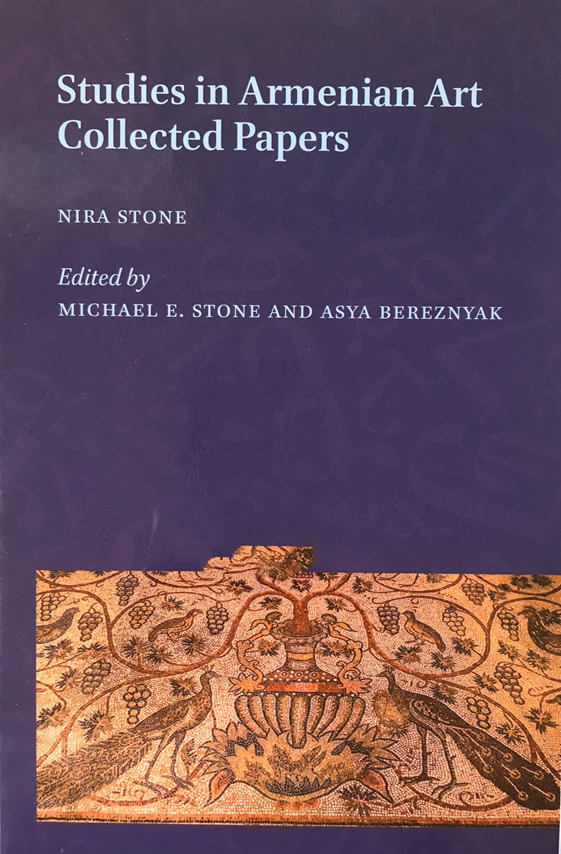

Scholars of various nations have pored over the rich legacy, but the quest is far from over, as a leading scholar, the late Dr. Nira Stone, points out in a newly released volume, Studies in Armenian Art, published by Brill, Leiden, the Netherlands, embodying “collected papers” written earlier.

The 262-page hardcover book, which is edited by Nira’s husband, leading Armenologist Michael Stone and medievalist Asya Bereznyak, is lavishly peopled with reproductions of manuscript pages and paintings, a large number in full color, but a few unfortunately bereft of their original splendor.

A detailed index helps facilitate one’s search, and an exhaustive bibliography points the way to further study.